BY JANET MANDELSTAM

Maria Krupoves says she was moved by the words of a French philosopher who wrote that there is nothing to do about the Holocaust except share the grief and mourn the victims together. Her way of sharing and mourning is to sing the songs of the ghetto “to remember and show the unprecedented courage of people who, being stripped of everything, were able to face a most possible death with singing.”

A native of Lithuania, Krupoves sings in 20 languages and speaks six fluently. She started singing Russian romances while studying Russian language and literature at Vilnius University, and soon she was recording songs in Polish, the language spoken in her home, as well as in Belarusian and Lithuanian.

It was when she learned that her grandparents had aided Lithuanian Jews during World War II that she became interested in Jewish music and songs, although she is not Jewish. “I had friends whose parents still spoke Yiddish; they taught me my first Yiddish songs. When I sang them to my mother, she cried, recalling her Jewish friends who disappeared during the war.”

Krupoves has recorded many Yiddish songs with their melancholy air. “That is the character of Eastern Europe,” she says. “The folk songs are often melancholic; most are written in a minor key” and they evoke feelings of “deep sadness, sorrow, laughter through tears. You cannot sing these songs without wanting to cry.” When she performs, she says, “Many native Yiddish speakers consider me one of their own.”

Krupoves has sung at Yad Vashem, Israel’s Holocaust memorial; recorded seven albums of folk songs; and can be heard in a number of documentary films, including four about the Jews of Vilna (Lithuania’s capital, now known as Vilnius). She first came to Bloomington in 2001 to participate in a conference arranged by Indiana University’s Jewish Studies Program. In 2006, she was invited back to lecture on the cultural life of the Vilna Ghetto and to sing its songs. It was here that she met her husband, Bloomington physician Daniel Berg.

Krupoves continues to perform and to lecture about Yiddish folklore and to sing the songs of other stateless cultures. Given the history of conflict in Eastern Europe, one of her goals, she says, “is to put together the songs of cultures that were in conflict in order to promote peace and understanding.”

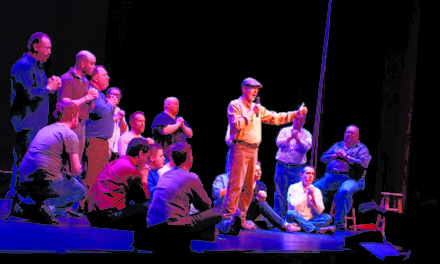

In April, she performed at the opening of the conference, Deciphering the “New” Antisemitism, arranged by IU professor Alvin Rosenfeld. For audiences unfamiliar with her songs she says, “I try to express the soul of the culture; I want the audience to love and understand it.”