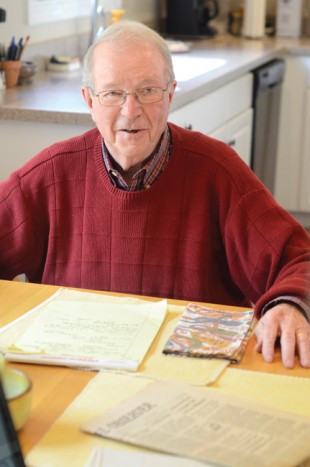

The Rev. Joe Emerson discusses his time in Selma, Alabama. Photo by Lynae Sowinski

‘I knew Martin Luther King Jr. before he was Martin Luther King Jr.’

BY MIKE LEONARD

The Rev. Joe Emerson’s face reddens and his eyes moisten when he’s asked his reaction to seeing the movie, Selma.

“It was very emotional,” he says. “I kind of relived it.”

The Bloomington minister was a schoolmate of Martin Luther King Jr. at the Boston University School of Theology and drove to Selma, Alabama, in the spring of 1965 to lend his support to the marchers challenging racial segregation and supporting equal rights for African Americans.

“I finally reached the point that it was either go to Selma or quit talking about it,” the former minister of St. Mark’s United Methodist Church says. “I said (to a writer for The National Journal), when my grandchildren ask me where you were when Selma was happening I didn’t want to tell them I was teaching a women’s Bible study class in Bloomington. The Selma experience was — I wouldn’t call it life-changing, but it certainly made me a part of who I am. I’m glad I went.”

Emerson, 83, grew up in Evansville, Indiana. “It was a Southern city north of the Ohio River. It was completely segregated,” he recalls. His first real experience with a more integrated society came with enrollment at Boston University in the mid-1950s, where he was a first-year student while King was “working furiously” to finish his doctorate. “The School of Theology is only about 300 students, so you had an acquaintanceship with everybody. I always like to say I knew Martin Luther King Jr. before he was Martin Luther King Jr.”

Like many in the clergy, Emerson watched the civil rights battles in the South, thought about King’s leadership, and encountered conflicting views about a minister’s role. Some believed it should be narrowly defined, to save souls and lead people to heaven. “‘Stay out of it’ was the attitude of almost all of my colleagues,” he remembers. Emerson believed that his Methodist tradition called him to preach beyond his own congregation, to live his faith, and to witness through his words and deeds.

He was a leader of Bloomington’s Human Relations Committee with the Rev. Ernest Butler when the news came down that white Unitarian Universalist minister James Reeb had been beaten and killed by white supremacists in Selma. Reeb, from Boston, was accompanied by Emerson’s close friend, the Rev. Orloff Miller, and had heeded King’s plea for the nation’s clergy to join the efforts in Selma after numerous protesters, black and white, were beaten on the Edmund Pettus Bridge on Bloody Sunday, March 7, 1965.

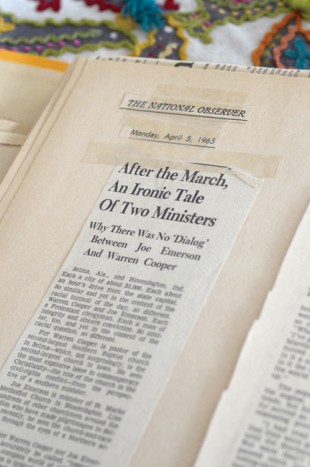

Emerson put together a scrapbook of newpaper clippings and letters from the experience. Photo by Lynae Sowinski

“I preached on a Sunday morning and left for Selma on Monday,” Emerson recalls. He had the support of St. Mark’s congregation and even bought a one-month, $100,000 life insurance policy from St. Mark’s Trustee Chairman Charles Beard before going. “Charlie said, ‘You’re crazy.’ And I did have a 7-year-old and a 5-year-old. But (wife) Gloria was right with me and said go. That took a lot of guts,” he says.

Emerson picked up a fellow minister in New Albany, Indiana, and drove to Selma. “Ministers wore suits in those days, and we drove to Selma in our suits. When we were in the white community we were treated very courteously. When we were in the black community, they were happy to have us. But when you crossed the line and were in between the two, that’s when things got scary. The state police were not happy campers. The only time I really felt fear was in the presence of those troopers.”

Emerson joined a night march that was broken up by police without incident. A couple of weeks later, the Bloomington Methodist and a Selma Southern Baptist preacher were profiled in a lengthy National Observer story contrasting their views in several areas, including Emerson’s social engagement stance and the preacher’s view that Jesus would not condone civil disobedience. Emerson still has many of the letters that readers of the Observer sent to him, ranging from congratulations to various forms of condemnation, many addressed, “Dear Comrade” or otherwise referring to him as a Communist bent on destroying the American social order.

Emerson served St. Mark’s from 1959–67 and, in the Methodist tradition, was assigned to other congregations in Evansville;

Columbus, Indiana; and Carmel, Indiana. Since retiring in Bloomington 20 years ago, he’s served on the founding board of Volunteers in Medicine and also on the board of the Shalom Community Center for people experiencing poverty and homelessness.

Looking back on his pilgrimage to Selma in 1965, Emerson says, “I do feel that I was on the right side of history. And, 50 years removed, I still think the most important role of what I accomplished was not only the witness down there but the witness back here. The dialogue between clergy and the role of the church in terms of social witnessing, I’m still persuaded that needs to happen.”