BY CARMEN SIERING

As a coach of the Bloomington Blades high school hockey team and Bloomington High School North lacrosse club team, Dave Appel understands the concern surrounding concussions in youth sports. “It’s one of my greatest fears,” he says. “Any time you have an open-contact sport where the speeds are high, the possibility exists on every single play.”

That’s one of the reasons Appel was eager to work with Nicholas Port and Steven A. Hitzeman, researchers at the Indiana University School of Optometry, who have been gathering baseline data on the eye movements and balance of athletes since 2010. So far they have collected data from more than 1,000 athletes at IU and area club and youth teams, all of which will be used to study the efficacy of the portable, sideline device they use to detect signs of concussion.

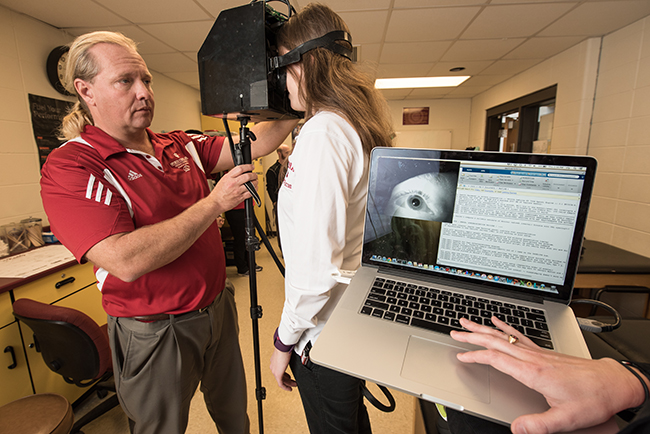

The protocol is simple. While standing on a Wii Balance Board, athletes don eyetracking goggles, then peer into a shoebox-size black box to track a series of images. Inside, a high-speed infrared video camera captures the athlete’s eye movements and sends the data to a nearby laptop.

Amanda Madsen works with Port and Hitzeman. A certified athletic trainer, Madsen spends weekday afternoons at either Bloomington North or Bloomington High School South. She performs typical trainer duties — keeping athletes hydrated, tending injuries — but if there is a concussive blow, she has the sideline device with her. It fits in a backpack, making it truly portable.

“The students see Amanda on a bi-daily basis,” says Orlin Watson, head athletic trainer at Bloomington North. “She’s pretty much at all the home games and she travels with football, so the kids know her. When it comes to collecting data for the study, they’re comfortable having her perform the procedure. Already knowing her puts them at ease.”

It helps too, that all of the athletes in the study have already been exposed to the device once, for their baseline test. If a concussion is suspected during practice or a game, athletes are checked out by medical staff, then tested on the spot and the results are recorded.

This is a much more objective way of diagnosing concussions, says Port, who notes that traditional baseline testing involves cognitive tests that some young athletes don’t take seriously. “For example, they take it as a college freshman and then, four years later, they’re trying to get into the NFL Combine,” Port says. “The coach, athletic trainer, or team physician is worried about a traumatic brain injury and tests them, and they do better than the baseline. There is no way that should happen. But their motivation is different.”

The tool Port and Hitzeman have devised involves tracking eye movement. “Eye movements are partially involuntary,” Port explains. “Nobody chooses how they move their eyes. You can choose what to look at, but you can’t choose if your eyes move quickly or slowly.”

Hitzeman, who has worked with IU Athletics for more than 30 years, says this research could change the way coaches and trainers handle possible concussive blows.

“For so long the diagnosis of concussion has been totally subjective,” Hitzeman says, referring to both cognitive testing and subjective medical tests that rely on athletes’ interpretations of symptoms for a diagnosis. “We’re looking at a totally objective tool. There’s a baseline, we run a test, and if you’re outside the limits, you can be diagnosed as concussed and you’re pulled out.”

Port and Hitzeman’s device is in the research phase now; nobody is being pulled from games based on its results.

“We don’t analyze the data on the spot, and we made a pledge to not make decisions based off data from an experimental tool,” Port says. “In fact, we wrote the code so it won’t give us results [on the sidelines]. We want decisions to be made on the standard of care.”

But many of those involved in the study are looking forward to the day when the device can be put to use. “Right now, all of the tools we have are symptomatic and subjective, and concussions can be under- or over-diagnosed,” Appel says.