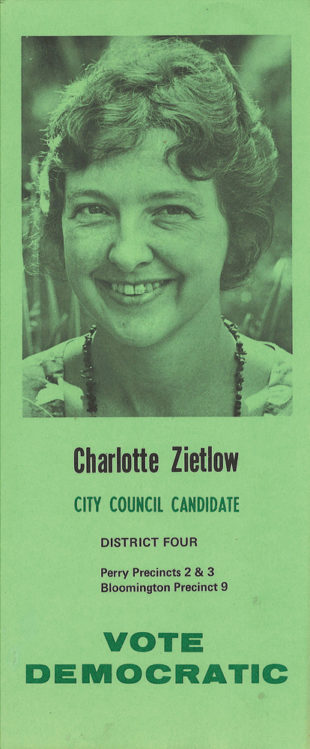

Charlotte Zietlow, 82, holds a Daily Herald-Telephone clipping from 1971. The headline refers to comments made by opponents during the campaign suggesting Zietlow’s Ph.D. in linguistics made her less qualified for office than incumbent Indiana University biochemist Harry Day. Photo by Rodney Margison

BY CARMEN SIERING

Charlotte Zietlow is arguably Bloomington’s leading citizen, having served as a City Council member, Monroe County’s first female County Commissioner, and in countless other political and community roles. Now, at 82, she’s written a book that chronicles the city’s political history, explores the fragility of democracy, and demonstrates how ordinary citizens have the power to change their government.

The book, Zietlow says, is a record of the city’s past that can serve as a model for changing our political present. “People think Bloomington has always been like this,” she says. “But 1971 was a turning point.”

As she notes, many of the things that seem quintessentially Bloomington weren’t always that way. She and her husband, Paul, moved here in 1964 when he came to teach English literature at Indiana University. Her first reaction to Bloomington? “I thought it was terrible!”

The couple came from Ann Arbor, Michigan, where they were graduate students. “Ann Arbor was a fancy town,” Zietlow says. “I came here and there were no sidewalks, no storm sewers. I was a cook and we could always go into Detroit and get any exotic ingredient. Here? The most exotic ingredient was paprika at the A&P.”

Zietlow says that while it was a huge adjustment, she stayed busy, finishing her dissertation in Germanic languages and caring for the couple’s two young children, Rebecca and Nathan. While she taught a few classes for IU, she couldn’t get a full-time faculty position. “This was the 60s,” she says by way of explanation. “Those were difficult times.”

Zietlow says that while it was a huge adjustment, she stayed busy, finishing her dissertation in Germanic languages and caring for the couple’s two young children, Rebecca and Nathan. While she taught a few classes for IU, she couldn’t get a full-time faculty position. “This was the 60s,” she says by way of explanation. “Those were difficult times.”

Difficult in many ways. “The spring of 1968 was horrible,” Zietlow recalls. “The assassination of Martin Luther King, of Bobby Kennedy. The Tet Offensive. The one bright spot was Prague Spring.” Paul was offered a chance to teach in Czechoslovakia through the U.S. Department of State, and to take the family with him. However, when the Soviet Union invaded, they thought their visit would be revoked. “How could we go with tanks in the street?” Zietlow asks now. “But we did go, for a year, with the children.”

While she had been politically active in the Democratic party in Ann Arbor, Zietlow says her time in Czechoslovakia really opened her eyes. “There was a law there that said you couldn’t speak negatively about the Czech government in a group of two or more,” she recalls. “But Paul and I could listen to the Voice of America criticizing the American government for the war [in Vietnam]. And I thought, ‘Democracy is fragile.’ It’s not something that just happens. You have to keep working at it.”

When she returned home, Democratic County Chair Ed Treacy asked her to run for City Council. “I said, ‘No. What do I know?’ But he said, ‘You’ll be surprised. You know as much as anybody.’ So I went to a City Council meeting.”

What she saw was a lot of men rubber-stamping the mayor’s proposals without any input from the public. “And I thought, ‘Gee, I can do better than that.’”

At the time, the City Council had eight Republican members and one Democrat. Zietlow says that in 1971, a group of eight or 10 like-minded Democrats decided to run on a slate. “We really worked together with a unifying vision of participatory democracy,” she says. When they won the primary, analysis by a nonpartisan group suggested they had a real shot at winning the election.

“We worked hard,” she recalls. “We ran a textbook campaign. We went door to door, we talked and we listened. We were all neophytes. We had never been in government. But we were smart and we cared and we won. We pretty much swept it!”

That election changed the City Council demographic from 8–1 Republican to 8–1 Democratic.

In the book, Zietlow recalls the first days of the new Council. “We turned this town around very quickly,” she says. “Our first meeting started at 7:30 p.m. and ended at midnight. We had lists of what we wanted to do and we did them.”

Zietlow notes that many of the issues they tackled, from economic development to planning and zoning, fundamentally changed Bloomington. “Major things happened then, and they are still more or less in place,” she says.

The book is finished and she has a working title—Nothing Doesn’t Count. “Because everything does,” Zietlow says. Now all that’s left is to find a publisher.

Zietlow says she wrote the book for three reasons. The first is because it is a chronicle of a turning point in Bloomington’s history. The second is because it is a good story. But what is most important, she says, is that it’s a story that can serve as a model.

“What we did seemed impossible at the time, but it wasn’t,” Zietlow says. “And this was something that ordinary folks did.”