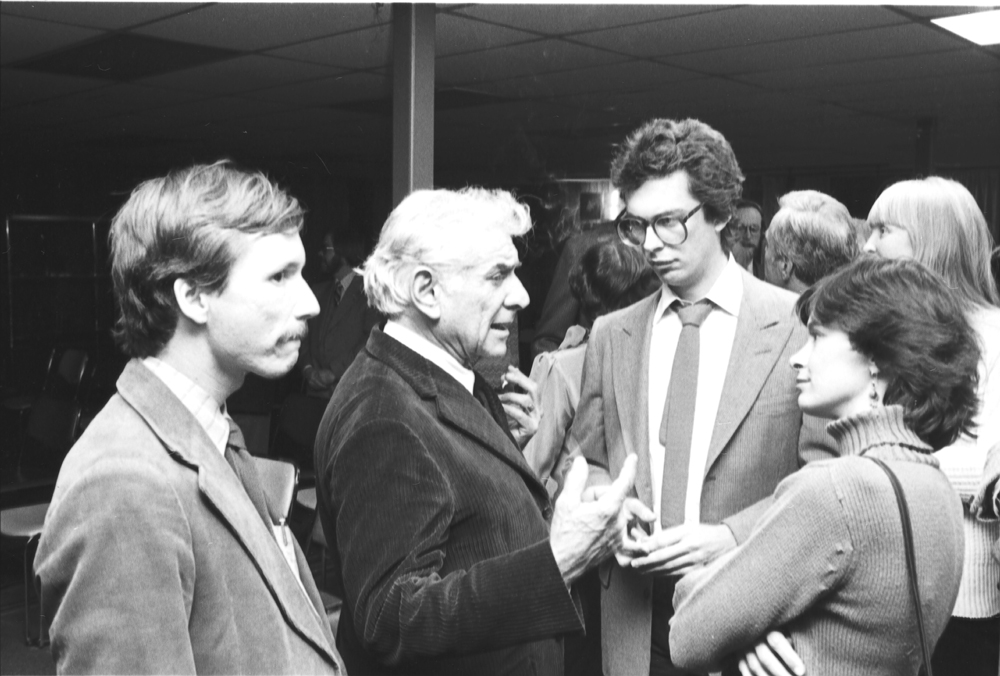

(l-r) Charlie Harmon, Leonard Bernstein, AQP Librettist Stephen Wadsworth, and Chef Ann Dedman. Courtesy photo

BY SUSAN M. BRACKNEY

Working for Leonard Bernstein was like trying to harness a tornado, according to Charlie Harmon, Bernstein’s former personal assistant-cum-music editor. In 2018, the world will celebrate what would have been Bernstein’s 100th birthday. Back in early 1982, the genius conductor-composer blew into Bloomington to escape New York City’s distractions and tap into student talent at the Indiana University School of Music.

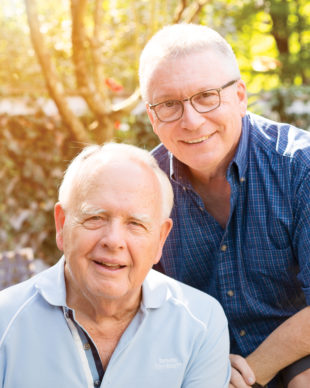

“What he really needed was a long immersion in musical thinking and dramatic plotting with his librettist,” explains Harmon, who was recently in Bloomington visiting with Charles Webb, former dean of the IU School of Music.

Bernstein made an indelible mark on both Bloomington and the music school. For several weeks, he stayed in a spacious Lake Monroe condo with manager Harry Kraut, librettist Stephen Wadsworth, chef Ann Dedman, and Harmon, who, upon hearing Bernstein’s 1982 travel itinerary, initially declined the assistant job. “In the first five minutes, I lost track of how many times I would be crossing the Atlantic,” he says.

Charlie Harmon, Bernstein’s former personal assistant (right), and Charles Webb, former dean of the IU School of Music. Photo by Martin Boling

The hard-driving maestro worked—and played—tirelessly. He had penchants for heavy smoking, drinking, sexual dalliances, and pushing boundaries. “He had a major sense of humor—provided you were willing to go along with it,” Harmon says. While at the Bloomington condo, Bernstein graffitied the wall with, “Leonard Bernstein was here and loved it.” When the condo burned down years later, it’s said that the owners were most distraught by the loss of Bernstein’s whimsical message.

Although he seldom ventured into town, Bernstein’s presence even affected Bloomington’s coffee scene. “Ann Dedman found a store that sold coffee. She bought several different kinds of beans and made a composite mix of them that would be what Bernstein would normally drink in the morning,” Harmon remembers. “They called it ‘The Maestro Blend.’ It was still for sale a couple of years later.”

One of Harmon’s most pressing duties? To ensure that Bernstein finished his new work, A Quiet Place, for its June 1983 premiere. Bernstein wrote at night and workshopped material with IU students during the day. “He wanted to hear the scenes as he wrote them, so we needed a rehearsal pianist who could sight read, and we needed singers,” recalls Harmon.

IU had long been on Bernstein’s radar. Kraut recommended using IU students for a tour of Bernstein’s Trouble in Tahiti opera in 1976. And later, Bernstein tapped IU to perform MASS: A Theatre Piece for Singers, Players, and Dancers at the Tanglewood Music Festival in 1988. On Bernstein’s recommendation, the IU student orchestra played at the grand reopening of France’s Opera Bastille in 1989.

Such was Bernstein’s affection for the music school that his family donated the contents of his Connecticut studio to it in 2009. Notable among the 2,100 items are a conducting stool believed to have been used by Johannes Brahms, and Bernstein’s Grammy, Emmy, and Tony awards.

“And there’s a beautiful photo of [legendary opera conductor] Fritz Reiner smiling,” Harmon says. “It’s supposedly the only photo of Fritz Reiner smiling,”

The collection is currently part of a traveling exhibit.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks