As part of Bloom’s Greatest Hits and in anticipation of this season’s Little 500 bicycle race, we look back at this story published in our June/July 2014 issue.

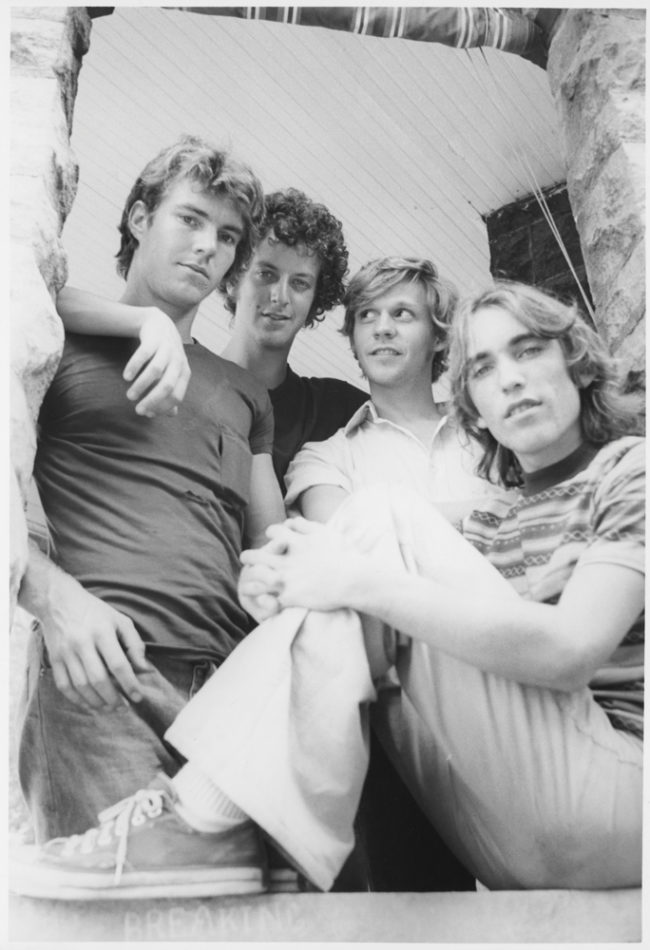

They were just four Bloomington kids contemplating life after high school in ‘Breaking Away’. But all four actors–unknowns at the time–went on to successful careers. (l-r) Dennis Quaid (Mike), Daniel Stern (Cyril), Dennis Christopher (Dave), and Jackie Earle Haley (Moocher). Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives

A Hollywood fantasy or an accurate depiction of Bloomington and its people?

BY MIKE LEONARD

Late last summer, a British film reviewer professed his love for Breaking Away, the Academy Award-winning 1979 movie set in Bloomington that will see the 35th anniversary of its premiere in July.

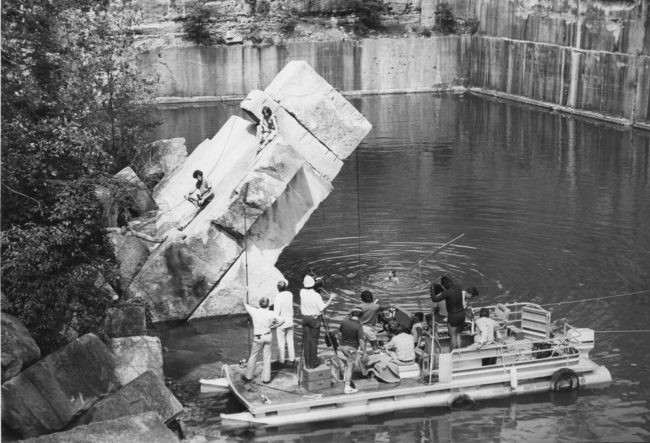

“I like films with a strong sense of place; where the location is almost a character in its own right,” Xan Brooks wrote in The Guardian. “Breaking Away cuts between a Bloomington campus of lavish college buildings and an abandoned quarry out in the woods. It then shows us the link between the two. Without Bloomington, there would be no Breaking Away. But without the quarry, there would be no Bloomington.”

The limestone quarries that cut through the landscape between Bloomington and Bedford not only created jobs over much of the 20th century and built iconic buildings ranging from the Empire State Building to the National Cathedral but also gave Bloomington and Indiana University a distinctive gray-white limestone appearance.

Scott Russell Sanders, author and distinguished professor emeritus of English at IU, mostly agrees with the British film writer. “One of the reasons Breaking Away stands out in the minds of many film viewers, viewers not connected to Bloomington, is that it’s one of those rare films that’s set in such a distinctive place that they’ve never heard of. You could come up with a long list of notable films before you’d find one set in such an unpredictable place.”

But despite the critical praise and widespread affection that Breaking Away still generates 35 years after the small-budget film became a surprise hit, some question just how accurately the film depicts the real Bloomington and the town-and-gown relationship that is a major theme in the movie.

“I had a lot of feelings about this movie. Not all positive. But, ultimately, they had a major impact on my life,” says Angelo Pizzo, who grew up in Bloomington and went on to write and produce the iconic place-specific films Hoosiers and Rudy. “A number of the characters in that movie seemed to come from another universe. They didn’t seem like Bloomington people at all. I never met a Dennis Christopher [the actor who played lead character, Dave Stoller]. The parents didn’t ring true. Nothing felt right.

“There was something about that movie that really bothered me and actually was the reason I wrote Hoosiers. I didn’t want to make the same mistakes,” Pizzo says. “Having grown up as a townie and a gownie, I never felt it was totally reflective of what was going on. Most of the kids, even at BHS [Bloomington High School], went to college. I never felt that socioeconomic divide. The country people, the hillbillies, versus the people who lived in the city, that was more the sociocultural difference than town and gown.”

Longtime teacher and township trustee, Dan Combs, agrees with this point. “It wasn’t just a divide between town and gown, it was a divide between country and town and gown. Harrodsburg, Smithville, Unionville, Stinesville, and Dolan were much further away than they are now,” he says.

Combs also notes that no one outside of the university, not even in the city or county, gave a hoot about the Little 500 bicycle race, and, contrary to the movie plot, no self-respecting local pined away for the opportunity to participate in it.

One thing everyone agrees the film didn’t get right was the term used for locals — Cutters. They were really called Stoneys because they worked in the stone industry, but IU graduate and Breaking Away screenwriter Steve Tesich knew he needed a different term because the drug culture of the ’60s and ’70s had put a new and undesirable connotation to the term, Stoney.

“I was bemused by the fact that Cutters were treated in the film as a derogatory term for townies when, in fact, in the stone industry the cutters were the next to the top of the hierarchy,” says Sanders. “The highest are the carvers, and right below them are the cutters. These were the foremen who knew the stone so well they knew what to cut and where to cut. It actually was an honorific to be a cutter.”

Filming on location made the Bloomington area akin to a character in ‘Breaking Away’, says film critic Xan Brooks. The film crew rented a pontoon boat to shoot this scene at “Slant Rock” at Sanders Quarry (commonly known as the Rooftop Quarry), south of Bloomington. Photo courtesy of the Indiana University Archives

Youthful conflict

There were inevitable youthful conflicts, just as there are in communities that don’t have a town- and-gown or a country and town-and-gown split. A favorite bit of mischief that Stoneys pulled on unsuspecting college students was called “snaking,” says Combs. “Carloads of Stoneys would drive around and through campus armed with 12-foot-long, soft-tipped, bamboo cane fishing poles. When a likely target was seen walking in the same direction as the car, the car would slow and a kid would hang out the window, tapping the pedestrian in the butt with the soft pole tip. Then the entire car would yell, ‘Snake!’ Wow. People would jump.”

And then there was the positively unnerving practice employed by the local kids with hot cars. “The driver would see a pedestrian or two, turn off the key, let off the accelerator, allow the engine compression to build, and then turn on the key. It was at least as loud as a 12-gauge shotgun,” Combs says. “People were, um, startled, to say the least.”

Required viewing

By any measure, Breaking Away was a highly successful film. Tesich won the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay and the movie was nominated for four others, including Best Picture. It also won a Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture: Musical or Comedy. The four young actors who played Bloomington buddies pondering life after high school all went on to successful acting careers: Dennis Quaid, Daniel Stern, Jackie Earle Haley, and Dennis Christopher.

Jon Vickers, director of IU Cinema, smiles at the mention of the extraordinary cast and says, “For me it still feels like a small movie, and I don’t mean that in a bad way. It feels like an independent film, a very genuine film. The film succeeds not only because of the landscape and the limestone manufacturing but also the race. Those don’t happen anywhere else, or at least in this fashion,” he says.

“The race is now an integral part of being here and I think that socioeconomic tension [created by Tesich] helps create conflict for the film, which is necessary,” Vickers says. “It’s another aspect that makes Breaking Away almost required viewing for anyone who’s moving to Bloomington. We watched it with our kids to get them excited about moving here. It makes you feel like there’s a real community here, that there’s something special about this place.”

Vickers says that while the race drama is exciting, it still takes a backseat to the setting and the limestone landscape. “The quarries are so iconic that many filmmakers who come here to visit [Werner Herzog and Crispin Glover included] ask about seeing them, and, of course, we try our best to accommodate them but they are now so difficult to get to because they’re on private property.”

Its finest moment

But the most important validation of Breaking Away and its singular sense of place, to Vickers, is an enduring image of the film’s four young primary actors, leaning back on a massive slab of limestone at the Rooftop Quarry, in documentary filmmaker Chuck Workman’s eight-minute, Academy Award-winning short, Precious Images.

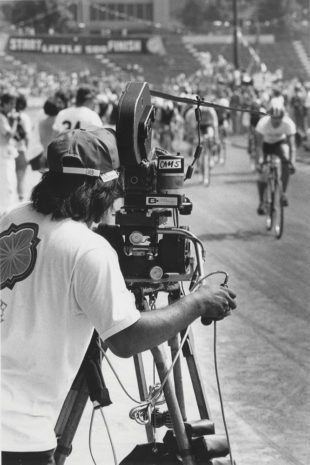

Race scenes were filmed at the former Memorial Stadium, which has since been demolished. Photo courtesy of Indiana University Archives

“Precious Images is the greatest love letter to cinema ever made,” says Vickers. “It was commissioned by the Directors Guild of America and it includes clips from 400 films covering the entire history of film. Imagine that. Out of the tens of thousands of films ever made, and all of the moments in those films that many of us will remember for the rest of our lives, Breaking Away is in there. That’s an amazing validation of the film right there.”

Scott Russell Sanders says, at its finest moment, Breaking Away beautifully compresses hundreds of hours of interviews that he and photographer Jeff Wolin amassed in producing their book, In Limestone Country (IU Press, 1985). “You know the moment in the film where the father tells the son he had worked on the buildings on campus but never went to see them?”

The exact quote, from the Dad (Paul Dooley) to his son, Dave (Dennis Christopher), is: “I was proud of my work. And the buildings went up. When they were finished, the damnedest thing happened. It was like the buildings were too good for us. Nobody told us that. It just felt uncomfortable, that’s all.”

Sanders says that when he interviewed current and retired limestone workers, many said they’d never gone to campus to see the products of their labor. “One gentleman said he just always felt like an outsider. He said, ‘I just think if I walked in there someone would say, “What are you doing here? What’s your business here?’”

Part of that attitude, the author says, comes from a humility among the limestone workers that he found perplexing. “Even the carvers wouldn’t accept the notion that they were artists in any way. You’d think that if anyone in the quarrying world or milling world would have accepted that they had artistic gifts, it would be the carvers. But they always said they were only craftsmen: ‘An artist makes things up out of his head. We go from drawings and pictures.’”

And while there could be no deeper sense of place than a civilization built literally on and out of the sediment of billions of marine animals that settled into the ancient tropical seas, and, over time, became limestone, Sanders says his attempts to explain that to quarry workers fell on deaf ears. “They weren’t curious about it at all. When I started talking about the limestone they quarried was 300 million years old, their eyes would just glaze over. To them, it was just rock.”

Like Sanders, Smithville native Dan Combs seized upon the father-son scene filmed in front of the massive stacked stone architecture of the Wells Library, as well. “My dad was a planerman in the stone mills. He cut the facade for Wells Library. He would not go look at it,” Combs says. “I always wondered how Tesich got inspired for that scene.

“Was Breaking Away accurate?” Combs asks. “I didn’t want to say it back then, but as we all idolize our youths, now, as an IU student looking in from outside at Stoney culture, yes, far more than I care to admit.”

Bloom’s Greatest Hit How True Was ‘Breaking Away”. . Is an interesting article that touched a nerve for me too. I was a student here in the 60’s and I certainly thought the strain between town and gown as portrayed was overblown. I spent more time at the “quarries” than I should have but we never called it “Rooftop Quarry”, it was rather referred to as “Long Hole” though everyone knew what the “rooftop” was. I saw Ken Sitzberger of the IU diving team do fantastic dives from there one afternoon. Its a shame what has happened to this cultural landmark.