As another spring season is upon us (despite the recent snowfall), and as part of Bloom’s Greatest Hits, we reflect on “Remembering Spring 1924, Bloomington,” a story from our April/May 2011 issue that celebrates the vibrancy of Bloomington during the Jazz Age.

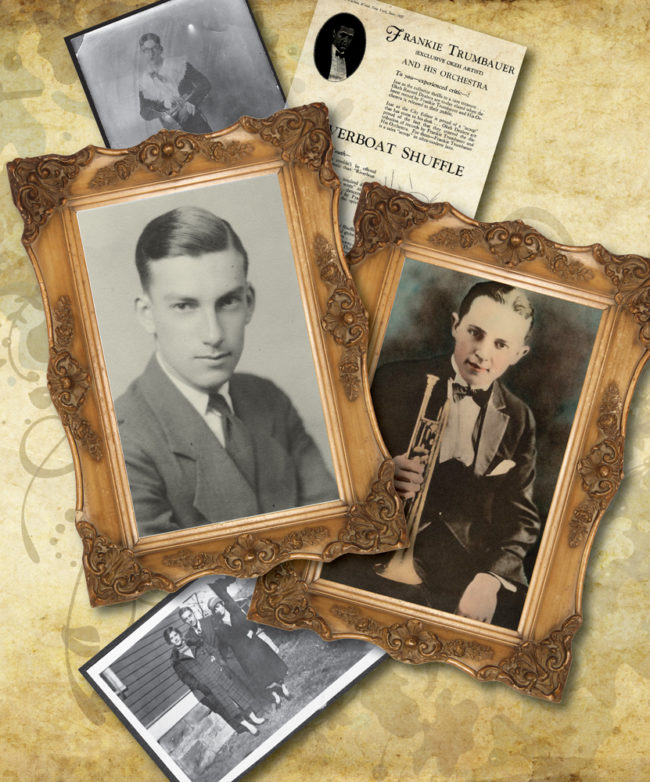

(opposite, clockwise from top left) Hoagy Carmichael in costume, possibly for a Dada play at the Book Nook with the Bent Eagles; an ad for Hoagy’s song “Riverboat Shuffle” recorded on the Okeh record label by Frankie Trumbauer and his Orchestra; colorized portrait of Bix Beiderbecke, taken not long before his arrival in Bloomington; Hoagy with his sisters Martha and Georgia outside of their house on Washington Street; portrait of Hoagy as a law student at IU.

BY DAVID BRENT JOHNSON • ILLUSTRATION BY CAROLE DIANE HESLIN

Photographs courtesy of the Archives of Traditional Music at Indiana University.

“Now these things happened in the spring of the year 1924 and they happened on the campus of Indiana University at Bloomington,” wrote Hoagy Carmichael in the opening pages of his 1946 memoir The Stardust Road. What happened that spring in this “town of some twelve thousand inhabitants and as many maples,” was this: The man who would write “Stardust,” the anthem of American popular song, brought Bix Beiderbecke, the man who would become one of jazz’s first iconic legends, to Bloomington for a series of campus performances. Hoagy and Bix played dances, listened to Stravinsky, drank a lot of bootleg liquor, and unknowingly began to create history.

But that was long ago, as a certain song once put it. And while the story of how Hoagy Carmichael wrote “Stardust” is well-known—he supposedly sat on a limestone wall at the edge of campus one quiet summer evening, thinking of lost love and the town around him, then dashed across the street to plot out the melody on the piano at the Book Nook—the story of his time here with Beiderbecke is less so. It’s possible, however, that “Stardust” would never have come to pass if it hadn’t been for Beiderbecke’s Bloomington visitations that distant spring.

Bix’s backstory

Beiderbecke had just turned 21 when he and his band, the Wolverine Orchestra, arrived that April. Born into a relatively prosperous German American family in Davenport, Iowa, he was written up in the local paper at the age of seven for his ability to play piano pieces entirely by ear; he didn’t learn to read music until late in his life, and then just barely. After listening to records by the Original Dixieland Jazz Band and jazzmen such as Louis Armstrong playing on the Mississippi River steamships that docked along the edge of Davenport, he became, in the parlance of Carmichael’s memoirs, a full-blown “jazz maniac,” and he took up the cornet, an instrument similar to the trumpet.

Easily bored, unable to stick with school or a job, Beiderbecke threw everything into his music. He was largely self-taught, he was not technically masterful, and yet he somehow became one of the first great soloists in jazz, helping to pioneer the jazz ballad style. The late historian and Carmichael biographer Richard Sudhalter praised Beiderbecke’s innovative ability “to be able to speak on several levels and arouse in the listener a mixture of responses.” Jazz historian Ted Gioia touts Beiderbecke’s influence on Bing Crosby, traces a line from his lifestyle to the counterculture of the 1960s, and calls him “the founding father of cool jazz.”

There have been numerous attempts to describe the impact of Beiderbecke’s sound. Guitarist and Indiana jazz legend Eddie Condon said it was “like a girl saying yes.” Fred Murray, an occasional Carmichael sideman who saw Beiderbecke play at a 1924 Bloomington jam session, told WFIU radio host Dick Bishop that Beiderbecke avoided the

tricks and artifices of his contemporaries: “He didn’t try to squeal like a clarinet, or play low like a flugelhorn…. He played within a range of two octaves, and what he did within those two octaves was something that most men have not been able to do before or since. He seemed to have opened the door to a new type of music.”

Hoagy (sitting at piano) at Gennett studio in Richmond, Indiana, with Hitch’s Happy Harmonists, recording his first composition, “Washboard Blues.”

Hoagy’s first impression of Bix

Since his untimely death in 1931 from alcoholism and pneumonia at the age of 28, Beiderbecke’s recordings have been treated as sacred texts of early jazz. When he and the Wolverines rolled into Bloomington in the spring of 1924, they had made only one record, and his reputation was just beginning to spread. Carmichael had already met Beiderbecke two years before, at a jazz speakeasy in Chicago.

“This fellow was rather slight and extremely young,” Carmichael wrote in his unpublished memoir Jazzbanders in 1933. “His eyes were peculiar and his silly little mouth fascinated me. His upper lip was red and he had a faint odor of gin on his breath. I learned that he had just come from a job, and it was the cornet that had reddened his lip.” Carmichael had heard him play, too, and had been unimpressed. But by 1924 Beiderbecke had made big gains as a player, and the Wolverines—a territory band made up mostly of Chicago musicians—gave him his first consistent vehicle for displaying his talents to audiences around the Midwest.

Wolverine saxophonist George Johnson, an occasional musical colleague of Carmichael’s, contacted Carmichael in early 1924, hoping to land some jobs for the band at IU. Carmichael set up a series of ten fraternity and sorority dance gigs for the Wolverines, spread over five weekends. “They were very appreciative, because they weren’t working any place at the time,” Carmichael later said.

Klansmen, Dadaists, bootleggers, political scandal, hot jazz, Midwestern industriousness, and a pastoral haven of youth: such was the world that Bix Beiderbecke and the Wolverines entered when they played their first gig in Bloomington.

Bloomington in the Jazz Age

Indiana University in Bloomington, like numerous other college campuses around the Midwest in the 1920s, was under the spell of “hot jazz,” the music swirling out of New Orleans and Chicago from the horns and pianos of artists such as Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton. Almost every campus boasted at least one working band. Duncan Schiedt, in his book The Jazz State of Indiana, says, “These young men who made up the college bands…were, like Hoagy Carmichael, taking their inspiration from the black musicians, and working out the style in endless hours of jamming around out-of-tune fraternity house pianos, in movie theater pits, and hanging around the bandstand when visiting orchestras played…. It was their fever for jazz which spread like an infection…and it was the seemingly tireless college dancers who made it pay.”

Hoagy often stayed at his grandparents “Pa and Ma” Robison’s house on Atwater Avenue. Hoagy likely worked out portions of “Stardust” on their piano.

“Bathtub gin” was a key element in Carmichael’s hot-jazz youth culture of the 1920s, both as a matter of consumption and of business. “Times were changing with the rush of a bullet,” he later wrote, discussing how some of his Bloomington friends quit school to “drive trucks guarded by imported mobsmen armed with Thompson submachine guns…. Hijackers stopped cargoes at interurban boulevards even in Indianapolis.” The Indiana Daily Student (IDS) and Bloomington papers from the spring of 1924 are dotted with state and national stories about bootlegger shootouts, ceremonial temperance-union dumpings of confiscated liquor, and political jockeying over Prohibition.

Bloomington was, in this new Jazz Age of America, metaphorically and literally at the crossroads of the culture. In 1910 the U.S. Census had determined the center of the country’s population to be at the Morton Street Showers Building. Showers was the city’s largest single employer in 1924, with about 1,500 workers; the limestone industry was also booming, employing about 2,000 area residents. Another institution was booming as well: the Ku Klux Klan, claiming a membership of nearly 1,600 in Monroe County (with headquarters just off the courthouse Square at 213 N. College), and exerting a strong influence over Indiana state government.

A circle of dreamy goofs…

It was a rainy springtime that year, forcing Hoosier farmers to delay planting their corn crops. It was also a turbulent season in Indiana politics; Governor Warren McCray was found guilty of mail fraud and sentenced to ten years in prison, a conviction that grew out of McCray’s antagonistic relationship with the Klan. Locally, the city of Bloomington was proceeding with plans to dam Griffy Creek and turn it into a lake to help ease the area’s ongoing water shortages. Indiana University was celebrating its centennial with a special pageant—and on and off the campus, a small circle of dreamy goofs and musicians were celebrating everything in their own peculiar way. Hoagy Carmichael was one of the central members of this circle, which called itself the “Bent Eagles,” but its leader was a musically gifted, poetically inclined student named William “Monk” Moenkhaus.

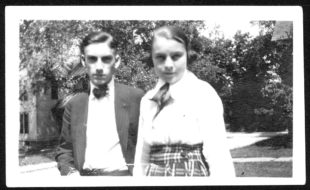

Hoagy with his college crush Kathryn Moore, whom Hoagy claimed was part of his inspiration for “Stardust.”

Moenkhaus had spent some of his adolescence in Switzerland during World War I, and, biographer Sudhalter writes, “He was apparently exposed to the Dadaist movement then taking shape in Zurich—or at least its intellectual fallout—and brought its principles back with him when he returned to study music in Bloomington…. In an intriguing way he was the exact antithesis of Bix: ‘Monk’ the creature of intellect, all left-brain domination, Bix was one of intuition. Together they formed a sort of yin and yang for Hoagy’s awakening consciousness.”

Moenkhaus, the skinny, spectral, music student, and the other Bent Eagles often held court and observed their strange, “anti-bourgeois” Dada-like rituals on Indiana Avenue at the Book Nook, “a randy temple smelling of socks, wet slickers, vanilla flavoring, face powder, and unread books,” Carmichael, who served as a sort of unofficial house pianist for the Nook, wrote in Sometimes I Wonder. “Its dim lights, its scarred walls, its marked-up booths, unsteady tables, made history. It was for us King Arthur’s Round Table, a wailing wall, a fortune-telling tent…. New tunes were heard and praised or thumbed down, lengthy discussions on sex, drama, sport, money, and motorcars were started and never quite finished. The first steps of the toddle, the shimmy, and the strut were taken and fitted to the new rhythms. Dates were made and mad hopes born.”

The first gig: Friday, April 25

Klansmen, Dadaists, bootleggers, political scandal, hot jazz, Midwestern industriousness, and a pastoral haven of youth: such was the world that Bix Beiderbecke and the Wolverines entered when they played their first gig in Bloomington. It was for the Booster Club Dance at the Men’s Gymnasium (part of what is now IU’s HPER Building) on Friday, April 25 at 8 pm.

That morning the IDS reported that more than 200 tickets had already been sold; there was a buzz building around the Wolverines similar to a modern-day hip, up-and-coming underground band that’s still too cool for the mainstream. The IDS also announced the opening of a barbershop for women on Kirkwood with the headline, “An Indication That the ‘Bob’ Is Here to Stay.” Cecil B. DeMille’s Triumph was showing at the Indiana Theater (today the Buskirk-Chumley). On the front page of the Bloomington Daily Telephone, a visiting New York City priest railed against the evils of birth control. On Saturday night the Wolverines played the Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity at 1026 E. 3rd St., and Bix Beiderbecke’s whirlwind season in Bloomington was underway.

Hoagy hears the “new” Bix

Hoagy’s Dada-like social group, the Bent Eagles, was “a small circle of dreamy goofs and musicians…celebrating everything in their own peculiar way.” William “Monk” Moenkhaus is seated back and center.

The IU campus was a growing place when Beiderbecke and the Wolverines arrived; enrollment had been climbing since the end of World War I, and there were now nearly 1,900 men and more than 1,300 women studying at the university.

The Wolverines quartered in Indianapolis throughout much of the spring, living in apartments just north of downtown; during the weekends they stayed over at IU fraternity houses, sometimes lingering into the weekdays. Carmichael found attending the Wolverines’ gigs difficult, as he was often working a date himself on the nights they played. On one of those first Saturday afternoons, however, the Wolverines set up at Carmichael’s Kappa Sigma frat house to rehearse, and he finally got a chance to hear Beiderbecke play—the newly advanced Beiderbecke of 1924.

Carmichael would recount this scene for the rest of his life. As the Wolverines started to warm up, “Every nerve in my body began to tingle,” he recounts in Jazzbanders. “My hands shook…. Bix played just four notes that wound up the afternoon party. The notes were beautiful and perfectly timed. The notes weren’t blown—they were hit, like a mallet hits a chime, and his tone had a richness that can only come from the heart. I rose violently from the piano bench and fell, exhausted, onto a davenport. He had completely ruined me…. I’ve heard Wagner’s music and all the rest, but those four notes that Bix played meant more to me than everything else in the books. When Bix opened up his soul to me that day, I learned and experienced one of life’s innermost secrets to happiness.”

“Something that he heard in either Bix’s tone or the way he put phrases together affected him very deeply,” Sudhalter said in a 2002 interview. “Deeply enough so that when he started to try his own hand at writing music, it was inevitable that his whole approach to phrase-building, to composition, would be based on what he’d heard coming out of Bix’s horn.”

“Bix lit the fuse that shot Dad out of the musical cannon,” says Carmichael’s son Hoagy Bix, whose middle name provides further evidence of the trumpeter’s influence. “He told Dad, ‘Look, you wanna be a lawyer, kid, that’s up to you, but there’s some stuff on the ends of your fingers…you got it!’ And you know, if Mickey Mantle tells you to put your spikes on, that you can be a great hitter…you put your spikes on.”

The “kid” was actually three years older than Beiderbecke, but his path remained uncertain in 1924. He was a musical Big Man On Campus, frequently mentioned in the IDS, and a member of two elite social societies. Yet his family’s finances remained precarious, endangering his enrollment status, and his pursuit of a law education was half-hearted. He was in danger of becoming “the eternal college student,” as he later mused in Sometimes I Wonder.

Says Hoagy Bix, now 73 and living in New York, “Dad was being prodded heavily by his mother to be a lawyer.” Lida Carmichael, described by Hoagy as “this little eighty pounds of wire and sweetness…wanted some income in the family—somebody, finally, to make a little money.”

The Book Nook: “a randy temple smelling of socks, wet slickers, vanilla flavoring, face powder, and unread books.”

A midnight serenade

Carmichael eventually earned his law degree, but his love of music ultimately brought him riches that would have been inconceivable to the young man who walked the streets of 1924 Bloomington. Driven by memories of his family’s hardship, the well-off songwriter would always put a high value on being financially comfortable; but it’s clear from his memoirs that he cherished the spiritual wealth of his early musical experiences in Bloomington, chief among them the spring with Beiderbecke. In Jazzbanders he recalls a “midnight serenade,” a ritual in which musicians were driven on a truck past the sororities and fraternities around 3rd Street: “By 1 am, everybody was at the Book Nook to start the serenade. It was drizzling rain, but the truck was at the curb. The piano and the Wolverines were placed aboard the truck, and every music-bug in school piled on it as the noisy contraption and a string of honking automobiles paraded to sorority alley…. Bix’s cornet playing was heavenly; he had never played in the open air at night, and the thrill it gave him was interpreted into the most uncanny phrases of beautiful notes.”

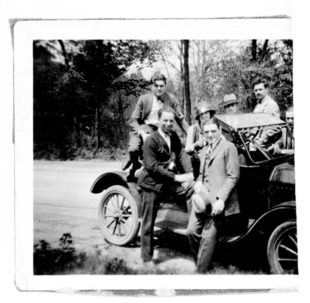

Hoagy with five members of the Wolverine Orchestra (sans Bix) and an unidentified woman in the spring of 1924. Hoagy is behind the wheel.

Years later Carmichael would visit this scene again in The Stardust Road, describing “an orchestra huddled in the back of a two-ton truck. Light cut dimly across a weird assortment of enchanted listeners as a cornet carved passages of heat and beauty in the night.” It’s a dream-like image, the young Bix Beiderbecke standing on the back of a truck moving along 3rd Street as he plays in the late-night rain.

Friday, May 2

The Wolverines returned to Bloomington on Friday, May 2, for a dance at the Sigma Chi house, located then, as now, at the corner of East 7th Street and Indiana Avenue. Carmichael managed to take the night off from his band to attend, and wrote in Jazzbanders, “The dance was the crowning affair of the season. It was more than that; it was such a riot that the organization barely escaped with its charter…. We were accused even of setting fire to the Delta Upsilon house, which burned to the ground shortly after the dance…. Jazz had reared its ugly head.”

The next night, the Wolverines played for Carmichael’s Kappa Sigma fraternity. The house sat roughly where the Acacia house is today; in Jazzbanders, Carmichael describes the frat “in an uproar.… Who wouldn’t have had a swell time with a band like that playing low and dirty! Vic Moore [the Wolverines’ drummer] was doing a voodoo dance in his chair, and he damn near bit his tongue off when he slipped in an important cymbal beat.… Vic’s cymbal lick and the break that Bix followed it up with relieved the tension and let us explode that awful pain inside. The dancers exploded too.… Bix’s chorus was usually the superb wind-up before the band would ease down soft and low.… Then a beautiful blast from Bix’s horn at the break in the chorus was the signal for the final dash while everybody went nuts.”

A monumental moment

“Take a drink of whisky that tastes like kerosene in your mouth and a blowtorch going down,” Carmichael wrote in The Stardust Road, recalling the exhilarating evenings, hungover mornings, and philosophical afternoons that he spent with Beiderbecke that spring. Lying on the floor of Hoagy’s Kappa Sig house, they drank bootleg liquor, joked, and listened repeatedly to Stravinsky’s The Firebird, taking in the splendor of the music, until the fateful moment when Beiderbecke said:

“Whyn’t you write music, Hoagy?”

Carmichael had already started writing; Jazzbanders includes an account of him in the Book Nook, spontaneously composing at the behest of Moenkhaus and other Nook regulars. But to be prompted by Beiderbecke, whom he idolized, must surely have moved his aspirations toward solidity. There was a mood, too, the kind of mood Carmichael said “comes only a few times in a lifetime,” and one that would forever inform his music:

“We lay there and listened. The music filled us with some terrible longing. Something, coupled with liquor, that was wonderfully moving; but it made us very close and it made us lonely too.”

Then the inevitable, staggering morning after, waking up in the Kappa Sig house with The Firebird and white-mule liquor still reverberating in his head, and looking over to see Beiderbecke, “a pale blond galoot needing a shave, sleeping in his tattered underwear, with his funny little mouth open, smelling like a distillery, his crumpled clothes piled on the dirty rug, the hole showing in the sole of his right shoe…. We went chugging down Indiana Avenue, our minds personally unoccupied, aware we were alive, surveying casually the small-town Sunday morning. People coming from church, smugly pious in their righteousness, dressed in their best, at peace with a world Bix and I never knew.” They were on their way to meet William Moenkhaus and his friends at the Book Nook.

Historic recordings in Indiana

The Wolverine Orchestra in February 1924 at Gennett recording studio to make their first record (featuring “Fidgety Feet” and “Jazz Me Blues”), which would create “a buzz” before their arrival in Bloomington two months later.

The Wolverines’ recording session at Gennett Records in Richmond, Indiana, on Tuesday, May 6, 1924, another cool and rainy day in a rainy springtime, is a small signal moment in the history of jazz and American popular song. Just three months earlier they’d made their first records at the label, which had already hosted visits from Jelly Roll Morton and a young Louis Armstrong. Gennett, which also recorded everything from so-called “hillbilly” music to novelty records and Ku Klux Klan propaganda hymns, would eventually be dubbed “the Cradle of Recorded Jazz,” and Beiderbecke’s handful of dates for the label in 1924 and 1925 would contribute to that legacy.

That Tuesday the Wolverines recorded two compositions that they had learned only recently. One was a jaunty tune called “Copenhagen,” and their recording that day would turn the song into a jazz standard. The other, a freshly minted composition, came from the mind and fingertips of Hoagy Carmichael. It was a “screwy and different verse” that he’d played for the Wolverines while they rehearsed the previous Saturday afternoon at his frat house. The Wolverines dug it, though they didn’t care for Carmichael’s “Freewheeling” title. When they laid it down at Gennett they called it “Riverboat Shuffle,” and there began what would soon be a widespread activity—recording Hoagy Carmichael tunes.

After the band returned to Bloomington, Wolverine saxophonist George Johnson woke up Carmichael and played him the record. “I listened patiently and quietly,” Carmichael later recalled. “I wasn’t thrilled—I was pleased, that was all—so much so that it made me sort of sad. I felt like crying over my little brain-child as a proud parent might cry at Thelma’s graduation exercises….”

A concert at Williams Jewelry

On Saturday, May 10, Beiderbecke and the Wolverines gave a noontime performance at Ed Williams’ music and jewelry store on the west side of the courthouse Square at 115 N. College. (Williams Jewelry Store stopped selling musical items long ago, but it’s still on the square at 114 N. Walnut and this year celebrated its 100th anniversary.) Williams took out ads in the IDS and the Bloomington Daily Telephone to promote the event, promising “A RARE TREAT SATURDAY…Wolverine Orchestra of Nine Musicians—Will Play Their Own Selections—As Played to Make Their Fox-Trot Records—Records Are—Fidgety Feet, Jazz Me Blues—Come and Hear Them All—And Other Record Numbers…”

There’s an unconfirmed report that Carmichael was with the Wolverines that day, playing his newly favored instrument of choice: the cornet. The courthouse Square was a popular destination on Saturdays (an April survey had counted more than 1,100 cars and 200 horse-drawn buggies parked downtown between 3 and 4 pm), so it’s likely that the performance drew some town residents as well as the Wolverines’ student fan base. That evening Beiderbecke’s band played a dance at the Student Building for the Women’s Self Government Association (W.S.G.A.) that required the musicians to wear tuxedos.

… taking in the splendor of the music, until the fateful moment when Beiderbecke said: “Whyn’t you write music, Hoagy?”

Friday, May 16

The beginning of the next weekend, Friday, May 16, saw the fifth annual observance of “Tacky Day” on the IU campus—a day on which the Boosters Club decreed that male students had to wear secondhand clothes. According to the IDS, those sporting neckties would have them forcibly removed. The tradition had actually grown out of the spike in clothing prices that followed the end of World War I.

That night the Wolverines played a dance for the Delta Upsilons—they of the recently fire-ravaged house—at Phi Gamma Delta at 631 E. 3rd St. The next night they were back at Sigma Chi. If they stuck around past the weekend, they could have taken in some cinematic sensationalism: “Come on to the Party, The Jazz Band’s Playing and Wild Youth Is Having Its Fling!” blared an IDS ad for Daughters of Today, coming to the Indiana Theater. “A Story of Youth and its new freedom, of boys and girls who sometimes mistake license for liberty. A story that is being enacted in every city and town today…. What is your daughter doing? Does she know more about Gin than Geography? Does she know more about Lovers than Love? Does she know more about Men than Mother?” The Wolverines were busy providing the soundtrack for the real-life version.

The last weekend

On Friday, May 23, a cool and rainy evening, the Wolverines began their last weekend in Bloomington by playing another dance for the W.S.G.A. in the auditorium of the Student Building. That same day the murder of 14-year-old Robert Franks in Chicago was reported in the IDS and the Bloomington Daily Telephone; his killers, Nathan Leopold and Richard Loeb, were not yet known or apprehended. The film adaptation of Indiana author Gene Stratton-Porter’s novel A Girl of the Limberlost was showing at the Princess Theater, and construction was about to begin for the Masonic Temple at the corner of 7th Street and North College. The Wolverines wrapped up their Bloomington stay with a performance at the Delta Gamma sorority house Saturday evening at 814 E. 3rd St., in what is now IU’s Military Sciences and ROTC building, just a block away from Carmichael’s Kappa Sig digs.

With the school year nearly over, the Wolverines moved on to Indianapolis’ prestigious Casino Gardens on the banks of the White River, and initially they were a hit—helped in large part by their many new fans from IU who came up to see them play. But business trailed off and they were let go. By the end of the year Beiderbecke had left the band, but he would return to Bloomington at least twice, playing the 1925 IU Prom with Jean Goldkette’s orchestra, and the 1926 Junior Prom with Frankie Trumbauer’s group. The IDS reported afterward that “Bix Beiderbecke…did not disappoint a single person who listened to his ‘dirty’ cornet playing, in its original form.” The campus reputation he had established two years earlier had clearly lingered and grown.

1927—a significant year

In 1927 Beiderbecke and Trumbauer joined one of the most popular ensembles in the country—the Paul Whiteman Orchestra. With their help, Carmichael got a chance to record his song “Washboard Blues” with Whiteman, playing piano and singing. (Whiteman’s regular vocalist Bing Crosby was kept close by in case Carmichael flubbed it.) Beiderbecke provided flourish with a dramatic cornet lead in the song’s up-tempo passage. It was Carmichael’s first moment of national attention, and another sign that a career in law was never to be.

Just three weeks earlier, on October 31, another event had taken place at the Gennett studio in Richmond, the significance of which would only slowly become apparent; Hoagy Carmichael had recorded “Stardust.” More than a year in the making, “Stardust” would eventually become one of the most-recorded songs of all time—and it bore the imprint of its composer’s friend Bix Beiderbecke.

“If you listen to ‘Stardust,’” Sudhalter said in a 2002 interview, “both in Carmichael’s melody and also in his piano solo, he was listening very strongly to Beiderbecke’s way of putting phrases together.… You hear it in ‘Skylark’ as well. You have a little two-bar phrase, another little two-bar phrase, and then a little longer phrase to sum it up. It’s a wonderful way of composing.”

The Indiana State Historical Marker in front of the former Book Nook (now BuffaLouie’s at the Gables), a popular hangout for Hoagy and his gang. Legend has it that Hoagy composed and refined much of “Stardust” at the Nook’s battered upright piano. The song is a standard of the Great American Songbook and one of the most-recorded songs of all time. Photo by Steve Raymer

What did Carmichael’s mentor think of the song? “It had become a hit,” Carmichael told an interviewer in 1969. “I’d never heard a word from Bix about the song, till finally, one day, very politely, he said, ‘Hoagy, that tune of yours—‘Stardust’—that’s a pretty good tune.’ Well, I felt so great! That Bix would even tell me that my tune was a good tune, you know.”

An early end

By 1929, Beiderbecke had gone into a state of accelerating decline, spurred primarily by his struggles with alcoholism. He left the Whiteman orchestra, tried some spells of rest at his family home in Davenport, and eventually returned to New York City, where he made his last recording date (“Georgia on My Mind”) with Carmichael in 1930. Concerned, Carmichael continued to visit him as his health worsened, but on August 6, 1931, gripped by pneumonia, hallucinations, and alcoholic exhaustion, Beiderbecke died. He was 28 years old.

Earlier that year William Moenkhaus had also died, not long after joining the faculty of the Detroit Conservatory; he, too, was only 28. Two of the centrifugal forces that had helped fire the first flights of Hoagy Carmichael’s imagination were already gone.

The Jazz Age was over—in more ways than one, in Carmichael’s opinion. “With the passing of Bix, my interest in music dropped about fifty percent,” he wrote in Jazzbanders. Says his son Hoagy Bix, “He felt that the jazz he knew had, to some extent, died with Bix. And Dad turned his musical thoughts to songs more like ‘The Nearness of You’ than to ‘Boneyard Shuffle.’ He became more commercial.” Asked if he thinks Carmichael would have written “Stardust” without spending so much time in Beiderbecke’s company that spring of 1924, he pauses and says, “Maybe not. Maybe not.”

Like a lost brother

Bix Beiderbecke remained central to the heart and soul of Hoagy Carmichael for the rest of his life. Several weeks before Beiderbecke died, he gave Carmichael the mouthpiece to his cornet, and Carmichael kept it as his mantle centerpiece for many years, right next to a statuette of William Moenkhaus. His 1946 memoir, The Stardust Road, laid the foundation for much of the enduring Carmichael legend and the Beiderbecke one as well, with the spring of 1924 playing a key role. Three years later Carmichael would revisit his friendship with Beiderbecke when Dorothy Baker’s Bix-inspired novel Young Man With a Horn was made into a movie, starring Kirk Douglas as a brilliant but troubled trumpeter, and Carmichael as his piano-playing, Hoagy-like friend. He continued to talk about Beiderbecke and his days in Bloomington to friends, family, fans, and researchers with reverence, melancholy, and humor, as if Beiderbecke were a lost brother.

Strangely enough, no pictures of Beiderbecke and Carmichael together have ever surfaced. “They were probably too drunk to stand up for a photograph,” Hoagy Bix jokes. The images we have come almost entirely from a handful of individual photos and scenes from Carmichael’s memoirs.

“The spring of ’24. Seems like the moon was always out that spring,” he wrote in The Stardust Road, “…seems like the air of those nights was doubly laden with sweet smells. The air was thick and soft and pale purple…. Of course it helps to be young, and I was young.” As was his pal and hero Bix Beiderbecke, “He of the funny little mouth, the sad eyes that popped a little as if in surprise when those notes showered from his horn.”

Walk, bike, or drive around Bloomington on some springtime eve, under the deep electric-blue skies that come just after sunset. Daffodils, crocuses, and lilies of the valley have all been blooming, and there seems to be a magical mist of green garlanding the trees; the world’s about to give way to summer. Nearly 90 years ago other people were out on these same streets at the same time of year, reveling and worrying, celebrating their youth even as it edged toward inevitable disappearance. Among them were two young artists, crossing paths in the heart of the heartland, high on life and music. A few years later one would be dead; the other would live, and write, and sing, and remember. Together, they carried the spirit of Bloomington into the annals of jazz history.