by CARMEN SIERING

As flames engulfed Notre Dame de Paris on April 15, concern grew over how the venerable cathedral could possibly be restored in this day and age. On NPR, 1A host Joshua Johnson asked an expert panel of guests a pointed question: Do we have the artisans—masons, carpenters, stained glass workers—capable of using traditional techniques to restore an 800-year-old building?

One guest, Randy Hollerith, dean of the Washington National Cathedral, mentioned that his institution employs two stone carvers and one stone mason, calling them “the last of their kind.” He went on to say, “It’s such specialized work now … to do limestone carving by hand, that there are few places where people can get this kind of training.”

Amy Brier, a local stone sculptor with an international reputation, says there is no need to worry. “They have people to fix it,” she says. “The French government owns all historic buildings and they have a strong infrastructure around restoration.” Brier should know—she worked as a carver and restorer for six months on the Cathedral St. Jean Baptiste in Lyon, France.

But she agrees that more training opportunities are needed, especially in the United States. As co-founder of the Indiana Limestone Symposium, a three-week event held every June at Bybee Stone Company in Ellettsville, Briar is doing her part. Started in 1996, this year’s symposium runs from June 2–22 and offers a variety of workshops from beginner to advanced, one-day to three-week sessions, and even workshops for kids.

“Part of my purpose with the symposium is to say stone carving is not dying,” Brier says. “I’m also on the Stone Carvers Guild and I will say that we’re getting older and we have fewer people coming up behind us. And that’s troubling. We’re looking for people to hand it down to.”

Mary Anne Sterling is a Limestone Symposium board member. She says the board is also concerned and wants to make a greater impact on the future of limestone carving.

“We’ve been talking to the City and County about how to expand the mission of the symposium,” Sterling says. “We’ve even thought about changing the name because ‘symposium’ can sound a bit elitist, but it’s open to everyone.”

Sterling says the idea is in its infancy, but it’s an exciting thought—to take what has been a series of June workshops

and create a year-round educational center.

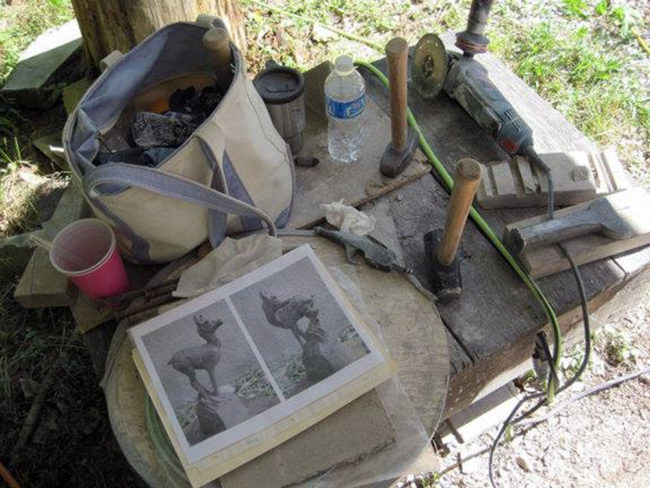

It wouldn’t take a lot of land or much of a building to get started. “To carve limestone, you need rudimentary tools and some shade, but you don’t need a lot of infrastructure,” she says. “You can see this at the symposium. So we can go anywhere.”

Sterling says the group hopes to have concrete plans in place by 2021, the 25th anniversary of the symposium.

Brier sees a bright future for limestone carving and for those interested in it. “A lot of stonework is artisan. I don’t like the art/craft divide, but there is a bit of a misunderstanding in this instance,” she says. Brier says you don’t have to be an artist to carve stone. “You have to be able to follow a pattern very well. Good craftspeople can replicate a design you give them.”

Sterling says a limestone center could be an educational and economic boon for the community. “This is where we say, ‘If you have the artistic ability or the interest in developing the skill set, there are jobs, right here in southern Indiana,’” Sterling says. “And, from what I understand, we also have a 500-year supply of our famous Indiana limestone.”

Visit limestonesymposium.org for more information.