by PETER DORFMAN

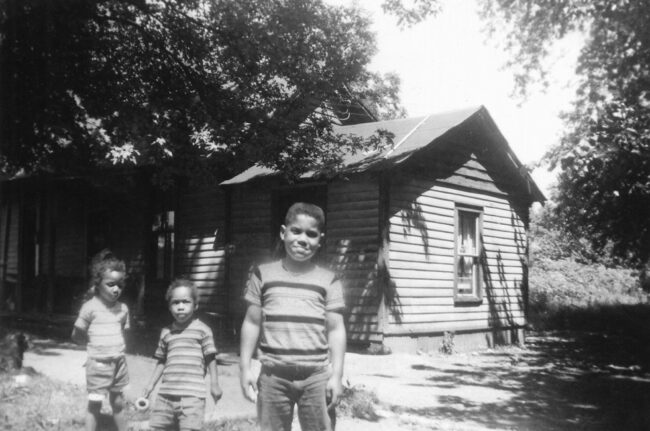

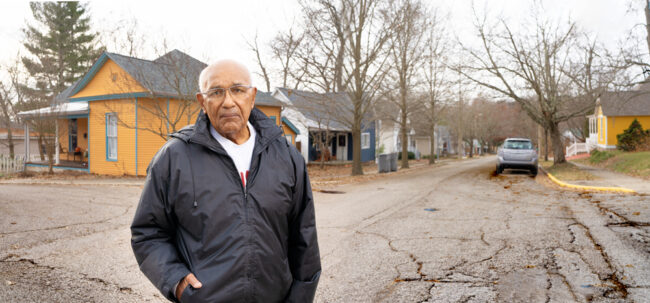

Oscar Bland, aka Kid Williams, was just 46 years old when he was murdered in 1953, in the front yard of his home at 1014 W. 8th St. as two of his children looked on.

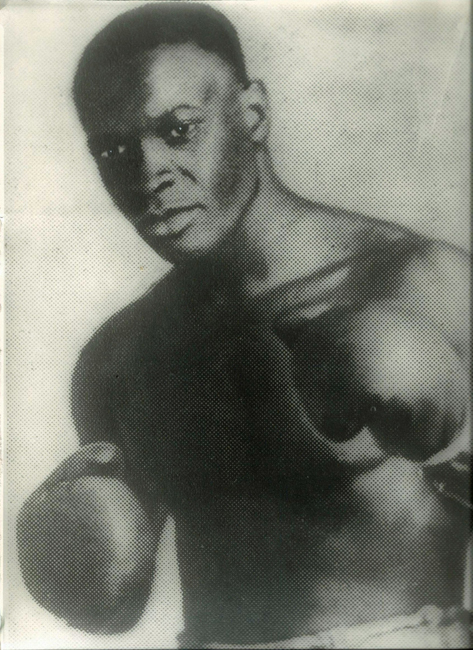

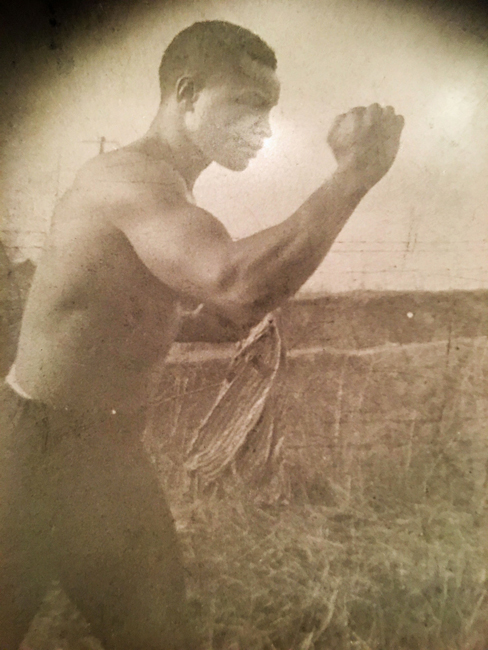

Oscar Bland may best be remembered as a boxer and trainer. In the 1930s he fought as “Kid Williams,” and sometimes as “Hard Rock Williams,” on the local amateur circuit and in exhibition matches at carnivals. He wasn’t a professional, but he was respected for his talent, discipline, and showmanship.

The nickname stuck with him long after he quit fighting. “I didn’t know him as Oscar Bland,” recalls the Rev. Marvin Chandler, who was a young minister at the Second Baptist Church on 8th Street in the early 1950s. “We all knew him as Kid Williams.”

Bland was born in 1907. “I was told Dad was born in Paducah, Kentucky, but I could never verify that,” his son Ronnie, now 82, relates. Oscar left home when he was 15 or 16, and moved to Bloomington when he was 19, according to the front-page story of The Daily Herald-Telephone the day after his murder.

NEAR WEST SIDE LIFE

When Oscar and his wife, Nellie, were raising their eight children on the Near West Side, it was a racially diverse, working-class neighborhood. The Blands were neighbors of Portia Thomas, who later became the Rev. Chandler’s wife. The Chandlers and the Thomases were strong church people, and upwardly mobile. The Blands weren’t, Portia recalls. In the black community at the time, that set them somewhat apart. But the families treated each other with respect. “They were a really good-looking family,” Marvin Chandler says. “Kid was a good-natured fella.”

Oscar held a variety of jobs, working at the Showers Brothers Co. furniture factory and as a janitor at the Second Baptist Church. He later worked at Skinner’s Tavern and the Eagles Lodge. “He always had two jobs,” Ronnie recalls. “He worked 15 hours a day.” Reportedly, Oscar was also something of a bootlegger and was arrested several times for illegal liquor sales.

“Dad wrestled a bear at a carnival,” Ronnie remembers. “They paid him $8. Mom was in the family way with one of the kids and that’s how he paid the doctors.”

But as time went on, Oscar began to make a name for himself not as a fighter or a sideshow entertainer, but as a trainer of young boxers. He set up a ring in the backyard of the family’s 8th Street home. (Like many of the original structures on 8th Street, the Blands’ house has long since been demolished and replaced.) “He had a punching bag, skipping ropes, everything,” Ronnie says. “He had a boxing club that he started in the late ’40s.”

The Near West Side was a different neighborhood then. Among the houses were several shops, like Boyd’s Grocery Store at 8th and John streets. A family named Hartfield ran a church in their basement.

GOLDEN GLOVES CHAMPIONS

Kid Williams’ club produced three young fighters that he coached and took to the Golden Gloves competitions for amateur boxers in Indianapolis. Two were Golden Gloves champions—a very big deal back then, when boxing was a bigger sport than it is today.

A white family by the name of Davison lived next door to the Blands. “We didn’t have water in the house,” Ronnie says. “We had a cistern, but it was dry. Mrs. Davison would let us take water from her place. Jessie Davison—she used to write country songs. She had a guitar and she would ask us what we wanted to hear. I always loved that song ‘Walking the Floor Over You’ [a 1941 hit for country musician Ernest Tubb]. She had us over and gave us kids biscuits and gravy.”

When he was 17, Willis Davison, Jessie’s son, told Oscar he wanted to be a fighter. Oscar took him on and eventually he felt the youngster was ready for the Golden Gloves competition.

“Willis was a southpaw,” Ronnie recalls. “When he hit you, most likely you were gonna go down. Daddy took Willis to Indianapolis on the Greyhound bus. He had two fights that morning and one in the afternoon. He fought this guy who’d had several professional fights, and Willis knocked him out in the third round. Dad came home at midnight and he was all smiles. Willis had his trophy, and they gave him a pair of yellow gloves.”

Another of Oscar’s club fighters was Julius “Judy” Thomas, a black youth who lived on 7th Street. He was a wild kid, fast, and his rivalry with Willis Davison was intense. “Judy was jealous of Willis and he wanted to fight him,” Ronnie says. “But Daddy wouldn’t let them fight.”

Thomas eventually got his shot at a title in Indianapolis, and became Oscar’s second Golden Gloves champion. His third contender was his son—Ronnie’s younger brother, Dennis. “Dennie was tall, the tallest one in the family,” Ronnie says. “When Dennie hit you, you knew you were hit. Dad took him to the Golden Gloves, but he didn’t win it.”

Ikey Elliott was another prospect. “He was a white fella, built real solid,” Ronnie says. “Ikey’s dad owned an ice plant at 7th and Morton, next to Hanson’s Pontiac. Daddy was training him. He wasn’t ready, but Judy took him to Indianapolis and Ikey fought this guy who’d had about 18 professional fights, and he beat Ikey up real bad. Boy, Dad was mad with Judy!”

Ronnie himself trained with Oscar for a year, initially as a matter of self-defense. “I went to Bloomington High School—it was integrated in 1951,” he says. “There was a heavyset black fella, Donny Manning. He was a bully, and he beat me up a lot. I went to Dad and said, ‘I’ve gotta learn to fight.’ Daddy said, ‘I’ve been waiting for you to come and learn to stick up for yourself.’

“This bully weighed 200 pounds and I was just a little guy, 135 pounds. One day I met up with Donny at the corner of 7th and Elm streets, by the Banneker School. We went down to the alley by the church [now the Mercy Mission Apostolic Faith Church]. Donny said, ‘I heard you’ve been training, so we’re gonna see what you’ve got.’ Well, he hit me one time, grazed my eye. I beat the daylights out of him and I had no more trouble.”

Oscar Bland’s fighters did roadwork on Sunday mornings. “We started at the Bloomington packing house on Vernal Pike—they used to slaughter cattle and hogs there,” Ronnie says. “We ran from there to the Ellettsville Road. It was four miles. Dad would be in a truck behind us. After we’d run, we’d get in the back of the truck. Then it got to the point where we’d run up to the Ellettsville Road and then back to the packing house. It’d be eight miles.”

The club boxers fought regularly in Crane, Indiana, against young soldiers, sailors, and marines—often black kids against white soldiers. “I fought a fella that was in the Navy, and I was only 13 years old,” Ronnie remembers. “This guy was about 19. And I whupped him.”

FATE INTERVENES

Oscar’s reputation as a coach and a role model grew and by 1953, he had a high profile in town. The Bloomington Police Department approached him with a plan to sponsor the boxing club. But fate intervened before the plan could be realized.

One July night, Oscar’s daughter Barbara had washed the family’s clothes and hung them out on the clothesline. Around 10 p.m., she went out to bring in the laundry. “A guy from the neighborhood, Charlie Anderson—he was a bad character, they called him Lost Charlie—he grabbed her,” Ronnie relates.

“My Daddy was just coming home from work, and he heard her holler. He ran back and caught Charlie and beat the daylights out of him. Charlie told Dad, ‘That’s the last time you’ll hit me.’ He ran home and got a shotgun, and he called Dad to come out.

“The kids tried to keep Dad from going, but Daddy walked out, and Charlie shot him right in front of the house, right in front of the kids. My sister Maxine came screaming and hollering. Twelve feet away, in the face, with a shotgun. It was awful. When it rained, it would wash the blood out from under the sidewalk.”

As a boxer, he was respected for his talent, discipline, and showmanship and later in life as a coach and role model.

Marvin Chandler was nearby at the Thomases’ home when he heard the shot. He and another neighbor went to investigate. “We saw the body lying there,” the Rev. Chandler says. “I called his name but he didn’t answer. We got there just about when the cops did. They threw a light on him. I’ll never forget that as long as I live.”

After the police investigation, the body was moved to 206 N. Elm St., the home of Oscar’s oldest daughter, Barbara, and her husband, Phil Drake Jr.

Lost Charlie Anderson was 53. “He was around the neighborhood a lot,” the Rev. Chandler says. “He was really lost. He had no family, no real home. People in the neighborhood fed him like a stray. He’d get drunk and they’d put him in jail. We weren’t afraid of him, though.”

Lost Charlie was known to police—he’d shot two other people, had been convicted of manslaughter in 1926, and served two years of a 21-year sentence. He lived at 515 N. Adams St., a boarder with a black family. Anderson fled the murder scene, but was arrested by Sheriff Fred Davis.

Davis later called the Rev. Chandler to say Charlie had been asking to see him. “I was just a green young minister,” says the Rev. Chandler, now 90. “I was so nervous. Charlie said, ‘Oh, Reverend, I would never have done that if I wasn’t drinking.’ I ministered to him until he went to prison. I told him I would try to go see him in prison but I never did get up there.”

Lost Charlie was convicted of murder, given a life sentence, and sent to the Indiana State Prison in Michigan City. When he was in his 70s, he was released. The Bland family went to court to stop him from returning to Bloomington. He died four years later.

After Oscar’s death, the family was split up. His daughter Barbara and her husband took in Ronnie and two siblings; other Bland children went to foster homes. Neighbors did what they could to help. “People mostly didn’t ask for pastoral help in those days,” the Rev. Chandler says.

Phil Drake Jr., Barbara’s husband, was one of the first black men admitted to the Indiana University dental school. He fought in the Korean War, but came back from the service to care for his nieces and nephews. “Phil raised me, my brother, my sister, and her little girl,” Ronnie says. “Then he went back to dental school. He went to officer’s candidate school and became a captain in the Air Force. He retired as a colonel.” Drake died in 2017 at the age of 87; Barbara passed away three months later at 86.

Oscar’s widow, Nellie, later married Joe Johnson, who had been one of the pallbearers at Oscar’s funeral. She died in 1987. She and Oscar are buried together at Rose Hill Cemetery.

Marvin Chandler officiated at Oscar’s funeral at the Day Chapel. “When Dad died, Willis Davison wanted to take his Golden Gloves trophy and put it on Daddy’s tombstone,” Ronnie says. “But I said, ‘Don’t do that,’ because somebody would steal it.” Where the tombstone now has an engraved image of praying hands, it once featured a portrait of Kid Williams on porcelain, but the picture was vandalized several times.

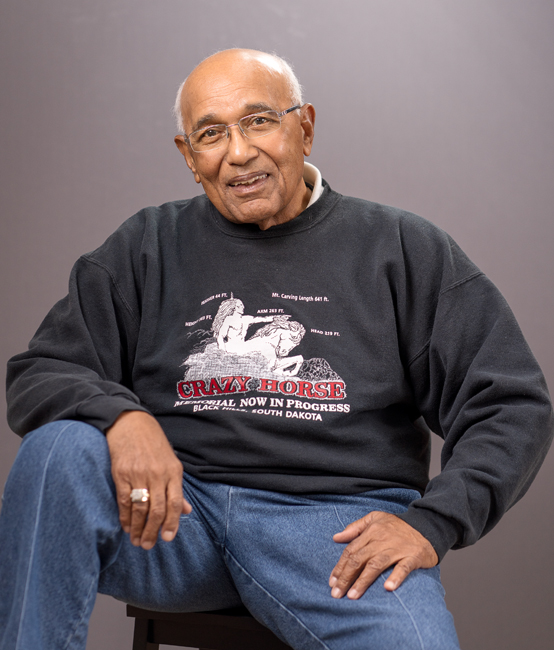

Ronnie, now 82, moved from house to house, all over the Near West Side, before marrying. He had three children, and later divorced. In 1986, he moved 10 miles north, building a house on Chambers Pike, where he still lives.

“I wanted all the family to leave the Near West Side because of the bad memories,” he says.

Ronnie was 15 when his father was shot down in their front yard. Looking back on that mournful day, he says, “I was just getting to know my dad.”