by CRAIG COLEY

For most people, staying at home is the best way to protect against exposure to the coronavirus. But the risks are reversed for those who sleep in community shelters. In mid-March, when “social distancing” had just entered the lexicon and the directors of Bloomington’s shelters were scrambling to safeguard the homeless population, one person quickly made himself indispensable.

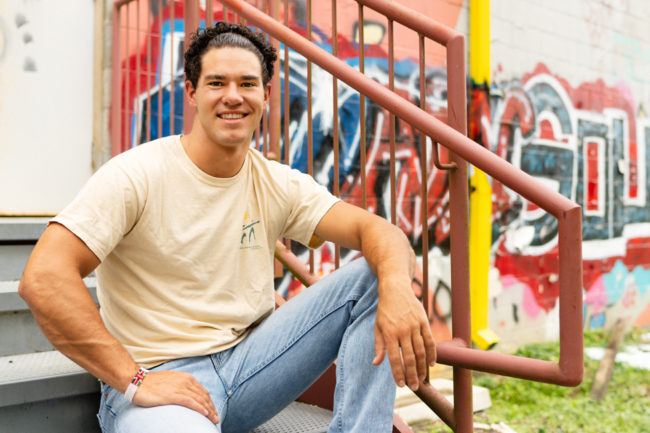

Sean Buehler, 25, is a third-year student at the Indiana University School of Medicine and a member of the board of directors of the Shalom Community Center, which assists people experiencing homelessness by providing a community center, support services, and a 40-bed overnight shelter. Buehler had been volunteering at Shalom since he was an IU undergraduate and knew the population. He had also worked for five years as a research associate for the Biosafety and Infectious Disease Training Initiative at IU and was familiar with best practices to prevent the spread of a virus like COVID-19. “He brought this knowledge base into a situation where all of us were amateurs,” says Forrest Gilmore, Shalom’s executive director.

His medical school activities on hold because of the pandemic, Buehler suddenly found himself with a lot of free time—time that he spent volunteering at Shalom’s day center at 620 S. Walnut, helping to develop protocols for the site. “It was my sanity the first three weeks of the pandemic,” Buehler says. “Being around the clients and the staff was a blessing for me.”

With a $70,000 grant from United Way of Monroe County, four agencies—Shalom, Wheeler Mission, Middle Way House, and New Hope Family Shelter—were creating an isolation shelter for people who had the virus or its symptoms. A warehouse space with offices at 300 W. Hillside Dr. was set up with 50 beds spaced at least 6 feet apart, and Buehler was asked to be its program supervisor.

He hired 12 people to staff the shelter and established protocols for its operation. In the rapidly evolving understanding of how the coronavirus spreads, Buehler was in regular consultation with local and state health officials. “I constantly felt like I was in over my head,” Buehler says, “but we made it work.”

It soon became clear that the Hillside site had drawbacks. Its shared bathrooms and large common areas risked exposing staff as well as clients who had symptoms but weren’t confirmed cases. Buehler learned about an opportunity that led to a $750,000 grant from the state, allowing the isolation shelter to move to a motel. This enabled the people who had been sleeping head-to-foot at A Friend’s Place shelter to relocate to the Hillside site, where they could practice social distancing.

In mid-June, Gilmore reported that no one he’s aware of in the homeless population had tested positive for COVID-19, though some had shown symptoms and stayed at the shelter while awaiting test results. The shelter also housed several people who had been made homeless because they contracted the virus.

On May 28, Buehler stepped down as the isolation shelter’s program director to resume medical school, but he remains on the Shalom board and the work he began continues. “He had an incredible passion for the work that was contagious for others,” Gilmore says. “He had the vision and the knowledge, and people were naturally inclined to follow his lead.”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks