by PETER DORFMAN

On July 4, 1999, Liana Zhou was driving her son home from a piano lesson when she found East Third Street blocked by police. They were investigating the drive-by killing of Won-Joon Yoon, an Indiana University graduate student who was shot by a white supremacist gunman as he was leaving the Korean United Methodist Church.

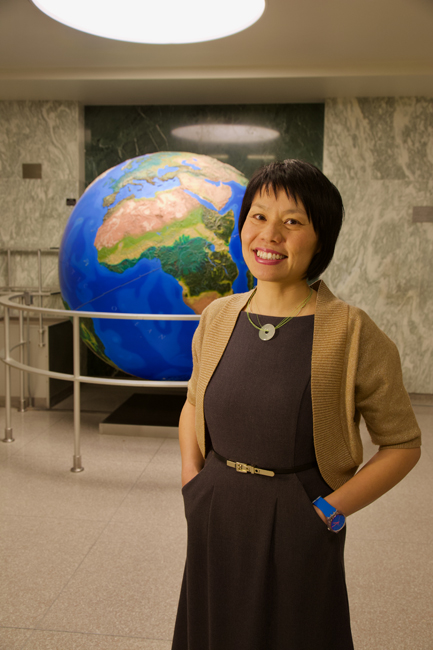

“I’m still processing it—how random it was,” says Zhou, now director of the Library and Special Collections at IU’s Kinsey Institute. “Anyone could have been the target—even in beautiful, progressive Bloomington.”

The 1999 killing shocked Bloomingtonians. And on March 16, 2021, the Atlanta shootings that killed eight, including six Asian American women, were a fresh reminder that when racist violence flares up in the U.S., Asians and Asian Americans are targets, just like other people of color.

Bloomington’s Asian Community

The national reckoning on racism in 2020 was fueled in part by former President Donald Trump’s anti-Chinese rhetoric during the onset of the COVID-19 crisis. But, says Melanie Castillo-Cullather, director of IU’s Asian Culture Center, “the Atlanta shootings surprised people who didn’t see Asian Americans as needing support or protection.”

Awareness of anti-Asian sentiment is likely to be magnified in Bloomington, which has a disproportionately large population of Asians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders, referred to as the AAPI community. By a 2019 U.S. census estimate, the U.S. is 5.7% AAPI. According to the website Statistical Atlas, the proportion in Bloomington is 9.6%.

Given the presence of IU—a large, globally oriented research university with a large international student cohort and strong Asian ties—this isn’t surprising. But although a significant number of Bloomington residents are AAPI, it is still difficult to delineate Bloomington’s Asian community, as there are no specific institutions that unify AAPI Bloomingtonians.

To create one would be difficult. Asia contains 48 countries with hundreds of distinct ethnic groups. Linguistically and culturally, Koreans, Chinese, Filipinos, and Asian Americans are as different from one another as Scots, Germans, Spaniards, and Italians.

Because Bloomington does not have ethnic neighborhoods where people with a common heritage settle together, Asian residents are scattered throughout the community, and although the Hoosier Acres and South Griffy neighborhoods have a relatively high concentration of AAPI residents (39.2% and 25.5%, respectively, according to Statistical Atlas), there is no one area of Bloomington where Asian residents live.

Bloomington has Chinese and Korean churches, as well as the Islamic Center (62% of the world’s Muslims are Asian), and the Tibetan Mongolian Buddhist Cultural Center, and IU offers extensive Asian studies programs, as well as an Asian Culture Center.

But no one, by any consensus, speaks for the local AAPI community. The City has commissions focused on the interests of Black and Latino communities, but none representing AAPI interests.

“People died in Atlanta, and these things can happen here. It did happen in Bloomington—in 1999.”

Microaggressions

And despite being an integral part of the Bloomington community, Asians and Asian Americans experience racism in Bloomington firsthand. Some of these occurrences are reported to the Bloomington Human Rights Commission, which tracks hate incidents, including those targeting Asians. Other occurrences are microaggressions—daily, racist interactions with which Bloomington’s AAPI residents have learned to coexist.

“It’s been small incidents, people driving by, saying ‘ching-chong’ kinds of things, or making gestures with their eyes,” says M.K. Chin, a Korean professor at the IU Kelley School of Business who has lived in Bloomington since 2014. “It was more about disrespect, not the kinds of violent incidents we’ve seen recently.”

Chin has had uncomfortable experiences both here and in State College, Pennsylvania, where he earned his degree and taught previously. “There have been incidents in larger cities, too,” he says. “I feel safer in these small college towns. I’m more worried about what my sons might go through in school.”

For residents who have experienced racism, it can be difficult knowing how to respond.

“There’s a delayed reaction,” says Liana Zhou. “You don’t realize you have been disrespected until you think about it later. You think, ‘I overreacted, I’m too sensitive.’ But as people speak up more, you can see a pattern.”

The anti-Chinese sentiment encouraged by Trump in 2020 became part of one of these patterns of racism for local AAPI people.

“The Black, AAPI, and Latinx communities have come together in solidarity over anti-Asian racism.”

“Just after the pandemic started, I had a cough,” recalls Victoria Cheng, a Chinese American who recently moved to Bloomington. “Some guy practically screamed at me to cover my mouth. I couldn’t really tell if that was because I’m Asian or if he was just scared of getting sick. It’s often hard to tell.”

Abby Ang, an activist who has worked during the pandemic to help individuals and families find food, shelter, and other resources, recalls one Bloomington couple who promoted anti-Chinese conspiracy theories regarding the virus and refused COVID-19 testing. “It came to a head when their daughter messaged me saying, ‘You Chinese people brought COVID to the world, and this is all your fault,’” Ang says.

The events of 2020 and accusations of the former president may have raised tensions for AAPI people, but anti-Asian bias didn’t start with COVID-19—or with Trump. Linda Stewart, a Bryan Park resident originally from Malaysia, was verbally assaulted during the Obama administration at an anti-war protest on the downtown Square. “A well-dressed white man called me a name—a racial slur—and told me, ‘If you’re not happy here, go back home,’” Stewart recalls.

Bloomington Human Rights Commission Hate Incident Reports track numerous incidents like these—fewer compared to anti-Black or anti-Latino incidents, and rarely involving physical assault, but demonstrating a clear history of bias against AAPI people in Bloomington.

Stereotyping and resentment

That bias may be obscured in part due to what advocates call the “model minority” myth.

The stereotype of Asians in America is that they are invisible, unspoken for, and unthreatening. The myth is complex, says Melanie Castillo-Cullather. Asians are largely fully assimilated into American society. But many whites view Asians in the United States as forever out of place—perpetual foreigners, even if their grandparents were born here. There is even resentment of Asian success in some segments of white society, she adds.

It’s a cliche, but it’s also AAPI people’s lived experience that white people have difficulty telling them apart. Mistaken identity has caused many embarrassing moments, which AAPI people experience as microaggressions. It has also led to incidents in which non-Asians have hurled COVID-19-related anti-Chinese slurs at AAPI people who are not Chinese.

“Anti-Asian racism has been part of the collective experience of Asian Americans since they first arrived in the U.S.—I mean since the gold rush,” says Ellen Wu, associate professor of history and director of the Asian American Studies Program at IU. “After the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 [providing an absolute 10-year moratorium on the immigration of Chinese laborers], the people who arrived from other parts of Asia to replace Chinese workers were also subject to discrimination and violence.”

Anti-Asian bias, especially anti-Chinese bias, often has a geopolitical connection. Chinese students, especially those in fields like informatics or engineering, have sometimes been suspected— even detained by federal authorities—as technological spies for Beijing, Wu notes.

The student experience

AAPI students often come to Bloomington assuming they’ll be safe from racism. Facing discrimination here has been a rude awakening. “They may ask themselves whether they made the right choice,” Castillo-Cullather says. “But that’s why there is an Asian Culture Center on campus. We’re there to make sure they don’t feel alone.”

The Center’s core mission is to provide nurturing support for AAPI students. But it also works with non-AAPI people who want to understand Asian culture and learn to be advocates and allies for AAPI students trying to find their place in Bloomington.

“Students are often uncomfortable but not really aware that they’ve experienced racial discrimination,” Castillo-Cullather says. “They don’t know how to identify it, much less how to cope with it. Some of the students feel it’s their fault—that they did something wrong. That’s really hard to listen to.”

A petition to the governor

Ellen Wu suggests that the 2020 upheavals at the Bloomington Community Farmers’ Market, including months-long protests over the presence of a vendor belonging to an allegedly white nationalist organization, represented a turning point for the town’s white liberals. “That experience revealed a kind of blissful ignorance,” she says, “that, for all its unique features, Bloomington has a lot in common with the rest of the country.”

Wu is an activist and leader of the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum Indiana Chapter. She and Castillo- Cullather were among the authors of a petition to Gov. Eric Holcomb asking the state government to establish a commission to examine anti-Asian racism in Indiana. “As of now, the governor has not responded to the petition,” Castillo-Cullather says. “He said something very general to the media about racism, but never anything specific about the issues we raised. People died in Atlanta, and these things can happen here. It did happen in Bloomington—in 1999.”

“The Black, AAPI, and Latinx communities have come together in solidarity over anti-Asian racism,” Castillo-Cullather adds. “When white people suggest Asian Americans don’t experience racism, they’re really saying they don’t see us as people of color. … This is where solidarity with other communities of color is so important.”

Non-Asian Bloomingtonians often want to declare their support for victims of discrimination, but there’s more to it than reading up on AAPI traditions or patronizing AAPI-owned businesses.

It’s an affirmative instinct for white residents to want to understand AAPI cultures, Castillo-Cullather says, but even well- intentioned people can, in the process, unintentionally reinforce stereotypes and the image of AAPI people as “other.” It’s better, she suggests, to simply get to know people as neighbors.

“Undoing racism is a process that requires a long-term investment in improving organizational structures and dismantling white supremacy,” Castillo-Cullather says. “There’s no quick fix.”

Websites of Interest

Indiana University Asian Culture Center

- asianresource.indiana.edu

Bloomington Human Rights Commission

- [email protected]

- Facebook: BloomingtonHumanRights

- bloomington.in.gov/boards/human-rights

Indiana Chapter of the National Asian Pacific American Women’s Forum

- napawf.org/chapters/indiana

Indiana University Asian American Studies Department

- aast.indiana.edu