Autumn isn’t what it used to be. Over the last few years, its onset has been delayed. The spectacular yellows, oranges, and reds of the changing leaves also have been affected. In part, cooler temperatures help to trigger trees’ fall color displays. But rising global temperatures have lengthened our summers and shortened the remaining seasons.

A recent paper in the journal Geophysical Research Letters suggests, “Even if the current warming rate does not accelerate … summer is projected to last nearly half a year, but winter less than two months by 2100.”

Droughts, extreme weather events, and even air pollution can further disrupt autumn’s natural processes. Fortunately, via the Nature’s Notebook “Green wave” campaign (magbloom. com/greenwave), you can help researchers to better understand how local trees are faring.

How It Works

Aside from springtime monitoring activities like tree budding, leaf-out, and flowering, Green wave participants can also track fall colors and fall leaf drop. Want to give it a try? For convenience’s sake, choose a special tree near where you live or work—picking a specimen you see often means you’ll be more likely to provide data on it.

Because they are widely distributed throughout many different climate zones, trees such as boxelder, red maple, and sugar maple are of particular interest to researchers. Still, there are plenty of other tree types on the Green wave tree observation list from which to choose. Ideally, you should be willing to make observations at least once per week. You’ll need to be able to estimate the percentage of tree canopy that still includes leaves as well as the percentage of tree canopy that includes colored leaves.

You’ll enter your data online or via one of the Nature’s Notebook smartphone apps. To get started, simply create a free user account, select the Green wave campaign, specify an observation site location, the tree type you wish to observe, and complete the online observer course training.

TreeSnap

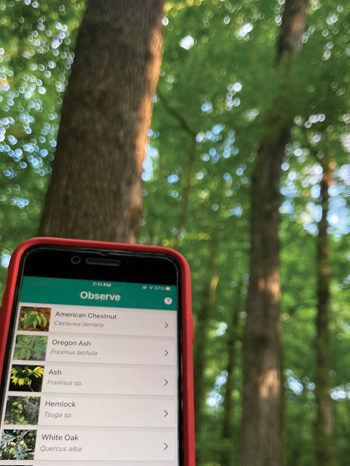

If you happen to have an American chestnut, butternut, elm, ash, white oak, or hemlock tree nearby, researchers from the University of Tennessee, Knoxville and the University of Kentucky’s Forest Health Research Center want to hear from you. They collaborated on the TreeSnap smartphone app (treesnap.org) to enable citizen scientists to report on the location and health of some of the country’s most threatened and rare trees.

By locating and studying the conditions around healthy specimens, researchers can better understand how some of these trees still manage to thrive—despite the many pests and pathogens they’re presently facing.

Certain about your tree’s species? Submit its location, photo, and details about diameter, height, canopy health, any signs of disease, and more.