by TRACY ZOLLINGER TURNER

OVER THE PAST 100 YEARS, THE INDIANA UNIVERSITY JACOBS SCHOOL OF MUSIC HAS BECOME AN ILLUSTRIOUS FORCE IN AMERICAN MUSIC EDUCATION. COUNTLESS EMINENT AND CELEBRATED MUSICIANS HAVE CALLED IT HOME— SOME AS FACULTY, SOME AS STUDENTS, AND SOME AS BOTH.

TALK TO ITS CURRENT AND FORMER DEANS, FACULTY, AND STUDENTS, AND THEY WILL TELL YOU THAT THE PLACE KNOWN SIMPLY AS THE IU SCHOOL OF MUSIC FOR MOST OF ITS EXISTENCE HAS CONSISTENTLY PUSHED BOUNDARIES. IT HAS DEFINED MUSIC EDUCATION IN WAYS THAT WERE DIFFERENT FROM ITS CONSERVATORY PEERS. IT HAS PUSHED THE ENVELOPE OF SOCIAL PROGRESS INSIDE IU ITSELF AND WAS THE UNIVERSITY’S FIRST MAGNET FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS. AND IT HAS ALSO BLURRED THE BOUNDARIES BETWEEN THE UNIVERSITY AND THE BLOOMINGTON COMMUNITY, MAKING LIVE PERFORMANCES AND ACCESS TO MUSIC EDUCATION EVER- PRESENT BENEFITS OF LIVING HERE.

“It’s the people”

Grammy Award–nominated jazz violinist Sara Caswell, now based in New York City, grew up in Bloomington, entrenched in the School of Music where her father, Austin, was a professor of musicology for 30 years. “It was like a second home for me,” she says. Whether it was the opportunity to see live Baroque music or jazz played here, or the lessons she began at age 5—long before entering as a college student and Wells Scholar in the late 1990s, “growing up with that sort of artistic, creative exposure is just— it’s a thrill.”

“Bloomington is a special place in the sense that there’s an electricity in the air, there’s a creative excitement and the same sort of energy you would encounter in a city like New York or Paris or Berlin,” she continues. “I think once you actually step outside of that zone, then you realize how special Bloomington is, and that the music school is, without question, one of the best in the world.”

The Jacobs School of Music faculty is filled with luminaries—each one a bright light within the constellation of a particular field of study or the mastery of a certain instrument. Some of those associated with the school are reluctant to name individuals on the basis of celebrity—the most famous or iconic really depend on the interests and passions of the person you ask.

“The quality of the school is determined by those important faculty members who were outstanding in their own fields and then, when appointed to the faculty of the School of Music, gave it its reputation,” says Charles Webb, dean of the school for nearly a quarter century beginning in 1973. “It generally turns out that what draws students is a particular teacher who is working in trombone or French horn or oboe. When we were able to find and appoint people of this quality it really set the school apart. Students found out, ‘If I go there, I really will have a chance to work with this person.’”

Gwyn Richards, who stepped down as dean just last year after 20 years at the helm, notes that many of the Jacobs School’s current faculty have come to teach at Jacobs as a second career after they’ve experienced success in the wider world of music. “I have always felt that the reason we have been and still are successful is because of the faculty—they know everybody and they’re well known in the profession.”

The Jacobs School was the first IU school to hire a Black faculty member—percussion professor Richard Johnson in 1951—and was an early champion of hiring female faculty.

The longevity of the leadership at the Jacobs School has also broken the mold. “I think the average nationally for schools of music is three years,” says Richards. But there has been a total of six deans in the Jacobs School’s entire, 100-year history.

“It’s the people,” says Richards, noting the contributions beyond the faculty. “There are people who have been staff members here for remarkably long periods of time and are every bit a part of the mission. And all of the audiences who come—the Bloomington community, the students, and all the people who made it possible for us to have the resources that we have.”

Early origins

Music has been made at IU since its founding in 1820, but for the first few decades, its presence was humble. There were extracurricular brass ensembles and choruses, an occasional class in music education, and the establishment of a 22-man marching band in 1896.

In 1904, IU President William Lowe Bryant sought permission from the board of trustees to create a school of music, seeing its value to a liberal arts education and career possibilities for those who wanted to study teaching. It took 15 more years to realize that vision, as faculty were added and a new department began offering five classes for credit. They took up residence in Mitchell Hall, a small, 60-foot-by-40-foot, two- story building (razed in 1991) that had been IU’s women’s gymnasium for the previous decade.

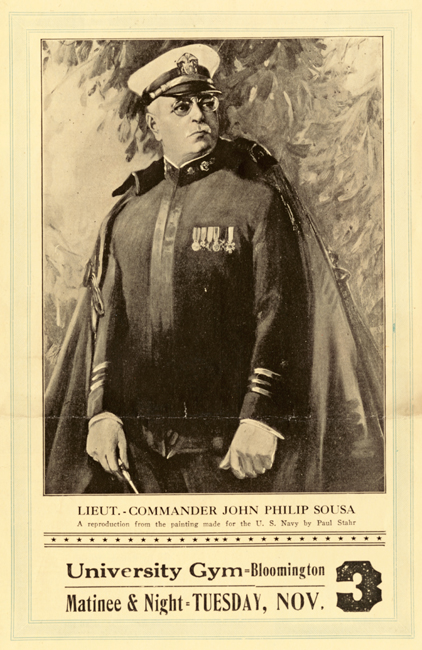

In 1919, violinist, conductor, and composer Barzille Winfred Merrill came from Iowa State Teachers College to lead the department, wanting to shift its focus from music education toward professional performance. When the IU School of Music officially opened in August of 1921, he became the school’s first dean. As its course offerings grew, so did extracurricular and recreational performances throughout campus and Bloomington. When John Philip Sousa visited in 1925, he anointed the IU Band—later to be named the Marching Hundred—“the snappiest marching and playing band in the country.”

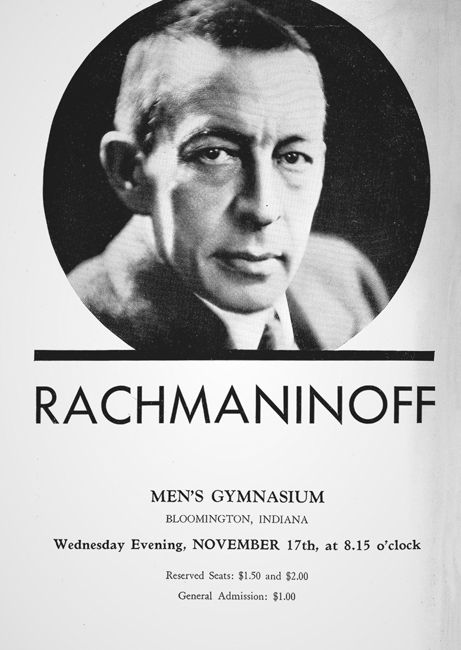

Virtuoso pianist Sergei Rachmaninov, the Vienna Boys Choir, and major city orchestras were brought to Bloomington to perform. Legendary songwriter and musician Hoagy Carmichael was studying law at IU but honing his jazz piano chops playing campus fraternity parties. The musical climate of IU was primed.

Setting the stage

Without a quality venue where musicians could play, IU’s music school was having difficulty attracting students who wanted to study performance. Merrill got a commitment from the board of trustees, which was matched by funds from the Works Progress Administration, to build a facility for the School of Music. The four-story limestone structure—later named to honor Dean Merrill in 1989—introduced dozens of practice rooms, a music library, and a 500-seat, air-conditioned recital hall to the campus.

Soon after the building opened in 1937, Herman B Wells became IU’s dynamic 11th president and Merrill announced his retirement. A fervent proponent of the arts (and a former member of the Marching Hundred himself ), Wells was supportive of the School of Music from the outset. He hired 32-year-old conductor Robert L. Sanders, its youngest-ever dean. Instead of adjusting the pendulum between music teacher education and performing arts, Sanders expanded the school in several directions—hiring internationally known music instructors, music theory and history scholars, and teacher educators to create a multifaceted approach.

The campus got another exceptional, much larger performance venue with the opening of the 3,700-seat IU Auditorium in 1941. It became a satellite home for New York’s Metropolitan Opera, which staged two productions a year in Bloomington from 1946 until 1962. Sanders made several more prestigious hires to the faculty, including soprano and frequent Metropolitan Opera performer Dorothee Manski. Sanders resigned in 1947 and Wells hired Wilfred E. Bain, who had already overseen tremendous growth at his alma mater, the University of North Texas, and was ready to ignite new changes in Bloomington.

A quest for excellence: The Music School builds a national reputation

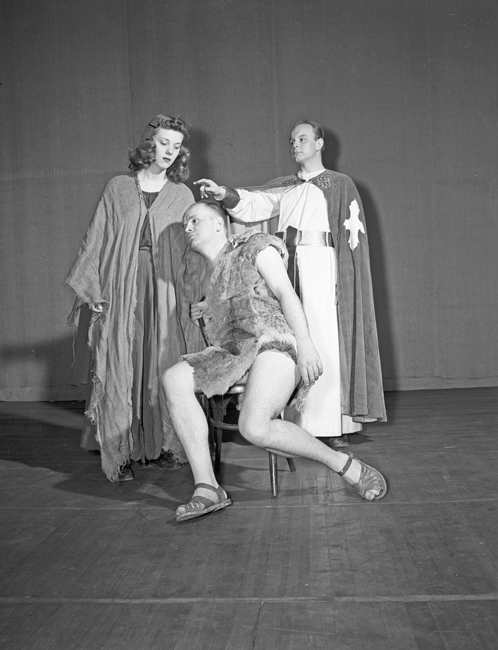

Dean Bain was tuned in to the steps that high-profile private conservatories like The Juilliard School were taking and saw to it that IU kept pace. He brought the well-regarded classical chamber group the Berkshire String Quartet in as the school’s long-term string quartet-in-residence, and the American Quintet as its resident woodwind ensemble soon after. But the quest for more widespread recognition of the School of Music leapt forward in 1949 when it staged its own interpretation of Richard Wagner’s opera about a knight’s quest for the Holy Grail, Parsifal. Professional performers, including faculty, were cast in lead roles, while students participated in other layers of the production. The reception from audiences and media around the region was so great that Bain decided that the school should produce the same opera annually, which it did for more than 20 years.

Mary Wennerstrom has been a witness and force in the evolution of the School of Music for two-thirds of its existence. She came to the school as an undergraduate student in 1957 and remembers the thrill of singing in the “heavenly chorus” in the first act of Parsifal from

the third balcony of the IU Auditorium. “Dean Bain had great, great aspirations about what we were going to do as a school,” she says. “I was part of all of that, and it was exciting.”

After earning her bachelor’s and master’s degrees, Wennerstrom was invited to join the music theory faculty in 1964, while still completing her doctorate. She remained on the faculty until she retired in 2016, having served as chair of the music theory department for more than two decades, as well as associate dean. She became the first woman to hold a dean’s title at the music school in 2002. During her time as a student, Bain required a great deal of recital attendance from students.

“That was how Bain was populating all these concerts,” says Wennerstrom. Rehearsal requirements became so tough in the 1950s that IU’s Health Services cautioned the faculty that many students were suffering from fatigue. While there are greater wellness resources nowadays, a core work ethic continues to define the student body. “The music students work very hard and are very disciplined,” says Wennerstrom, noting that in recent years, even the law school took note and “began offering special scholarships to some of the [music school] undergraduates that are interested in law because they are so detail-oriented.”

During Bain’s years as dean, he continued to populate the faculty with known virtuosos and stars-to-be in both performance and scholarship. Several came to the United States as refugees before, during, and after World War II. Pianist Menahem Pressler fled Nazi Germany in 1939 and embarked on a successful international solo career before joining the faculty in 1955. Now 98, he is still teaching. Renowned cellist János Starker, who was born in Hungary and survived internment by the Nazis, was appointed to the faculty in 1958 and continued to teach until his death in 2013. (His two older brothers, both gifted violinists, were murdered by the Nazis.)

Rehearsal and performance facilities lagged student demand. “We had a Quonset hut where the Musical Arts Center is now,” says Wennerstrom. “It was one of the old, World War II airplane hangars. It was serving as the stage for the opera theater. And there were a lot of very small rooms where I had a couple of classes with only enough space for an upright piano and a few students clustered around.” Merrill Hall, which Wennerstrom says was commonly referred to as “The Square Building” got its cylindrical neighbor in 1960—the Music Annex, a.k.a. “The Round Building,” which introduced 100,000-square feet of space. Student enrollment almost doubled during the 1960s, and 50 more faculty were appointed, including young alumni music theory scholars like Wennerstrom and Malcolm Hamrick Brown, a pioneer of Russian music studies. Composer and faculty member Juan Orrego-Salas established the Latin American Music Center in 1961, which still “fosters the academic study, performance, and research of Latin American art, popular, and traditional musics” at IU.

Jazz also began to make a formal entrance into the curriculum. Alumni David Baker, who Webb describes as “a major jazz musician before we appointed him to the faculty,” established a Jazz Studies program in 1968, which he chaired for almost 50 years. Under his tenure, IU began to offer the first jazz degree in the nation. The emergence of new technologies informed other enterprising areas of study. Greek-French music theorist Iannis Xanakis, a pioneer of computer-assisted composition, founded the Center for Mathematical and Automated Music in 1967, which has since evolved into the Center for Electronic and Computer Music.

The ongoing importance of the opera program also led to the appointment of ballerina Marina Svetlova, who had been the lead dancer at the Metropolitan Opera. She would chair that department for more than 20 years. “Dean Bain’s interest in opera was unusual for that time in that it covered all of the aspects of production of opera … and you cannot have an exceptional opera production without ballet,” says Webb. “Opera

is a cross-section of all of the arts and it demands this kind of cross-section of abilities. We had the opportunity to make these kinds of appointments because of the backing of Herman B Wells. He was interested in music—especially interested in opera—and willing to support it at critical times.”

Meanwhile, campus performance facilities were also set to take a very big step forward. In 1962, Bain and a group of School of Music faculty and staff went to Europe to investigate “every major opera house since World War II,” says Webb. The group wanted to learn “what they were doing in lighting, what they were doing in sound engineering, and all the various aspects of production” in order to create something truly state-of-the-art at IU.

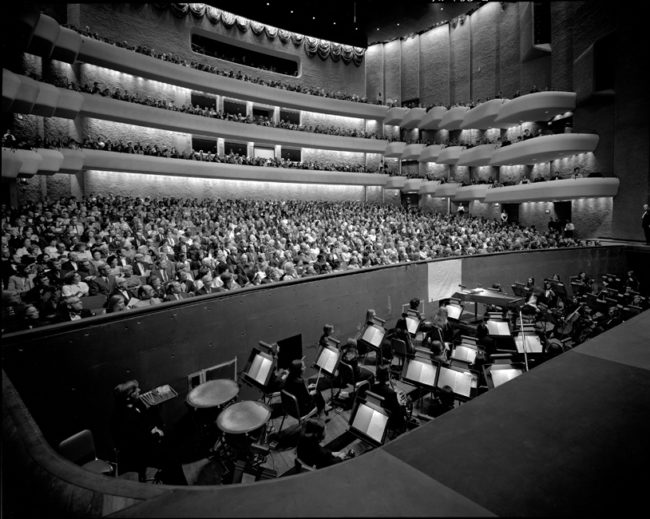

The Musical Arts Center (MAC) was ultimately modeled after the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center in New York City. The stage of the $11.2 million, 1,460-seat venue has a motorized floor with sliding stages engineered to move scenery quickly. Mozart’s Don Giovanni was its inaugural production in 1972, but Bain planned a later, week-long celebration. Crammed full of performances and the dedication of the 40-foot sculpture by Alexander Calder, Peau Rouge Indiana, that stands in front of the MAC, the showcase brought the school national press.

“The MAC gave us this performance facility that really was second to none, not just for operas but also for symphony orchestras, for bands, for chamber music,” says Webb. “To have a hall like this is unheard of in most academic institutions and even most professional facilities.” Bloomington, New York City, and Milan are the only cities in the world that share the capabilities of the MAC, according to Webb.

Ascending to the international stage

When Bain stepped down in 1973, Webb, who had earned his doctorate from IU in 1964 and become associate dean in 1969, was chosen to fill the role. Like Bain, he would spend more than two decades at the helm of the school and raise its profile even further—from national acclaim to international.

Webb’s longtime friend and colleague Henry Upper also came to IU as a doctoral student, joining the piano faculty in 1971. He was the chairman of the department before holding several administrative positions, including associate dean of external relations. “Dr. Bain had this interest in opera but also in producing what I would call ‘the thinking musician,’” says Upper, noting that many European conservatories of music have such a laser-focus on instrument mastery they can be “almost like trade schools.” But at the music school that Upper saw take shape under both Bain and Webb, “there is a place for the study of the instrument, but there is a great place for the study of the structures of music through music theory and through history. … If Charles [Webb] had a belief in the overall mission of the school, it was to make a thinking, complete musician.”

Two areas of study that he wanted to expand “to have a complete music school” were contemporary music and early music (prior to the dawn of European classical music in 1750). Scholar Thomas Binkey founded the Early Music Institute at IU in 1979 and was “a major figure in the development of early music,” says Webb. “When we were able to attract him to the faculty, this was a major part of the development of the school.”

Webb broke away from one of Bain’s hallmark practices immediately—instead of putting faculty or invited artists in the lead of productions, he made IU students center stage. “I had access to the singers, I heard them in auditions,” says Webb. “It occurred to me that we have the quality here to get done what I am hoping we can do. And it would give students a totally new perspective while they were here. And I think it worked.”

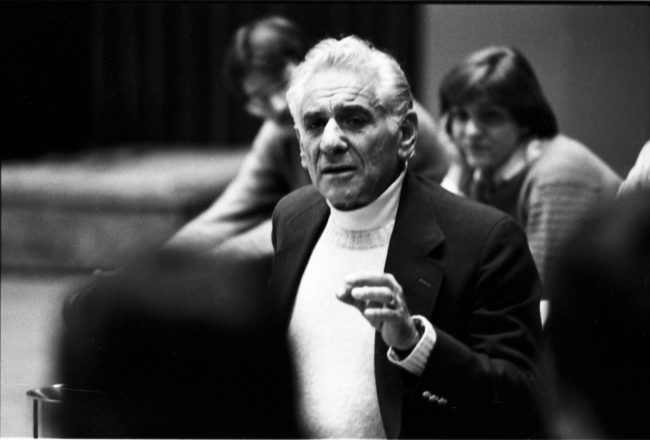

On the wings of that particular mission, IU students not only took the stage more often in Bloomington, but also around the world. “It was the performances we chose to do in New York that brought Leonard Bernstein’s attention to us,” says Upper. The renowned composer and conductor came to IU for a two- month residency in 1981 to work on his opera, A Quiet Place.

“He was so mobbed that he could not really get his composing done, so he thought he would come here to the quiet Indiana countryside,” says Upper. “When he was here, he would come in and just go through the halls and say to some singers he would hear in a practice room, ‘You know, I have been writing this today, would you try it out for me?’ He casually had a lot of experience with our students.”

The long relationship between Webb and Bernstein led the Bernstein family to donate all of the contents of his composing studio in Connecticut—a Sears kit building behind his home—after his death. “When it came time to distribute the documents, scores, we were absolutely bowled over when they suggested that all of that come to IU,” says Webb.

Gwyn Richards was dean at the time of the donation (2009), and was overwhelmed by the contents of the studio, which included Bernstein’s composition desk, and a stool that was given to him by the Munich Philharmonic “because he was such a proponent of Mahler” that curiously has the initials “GM” underneath. There is a portrait of Bernstein drawn by pop music icon Michael Jackson and “a lot of music and other writings and things that are really amazing,” Richards says. The contents will be eventually housed together officially in a replicated Leonard Bernstein Studio that will be used by visiting faculty.

By the mid-1980s, it became evident that the school’s reputation had become truly global—there were students from 41 countries in attendance. “We became the most international school at this state university,” says Upper.

One of Bloomington’s own

Bloomington-born violin prodigy Joshua Bell also became a student at the School of Music at that time. He had attended the newly created IU String Academy, where he studied with founding director Mimi Zweig. Influential classical violin master and faculty member Josef Gingold had also been mentoring him with private lessons since he was 12 years old. Bell’s career was already in flight by the time he entered college—he performed his debut at Carnegie Hall with the St. Louis Orchestra at 17 and had a deal with record label London Decca by age 18. He remains a force in contemporary classical music, having performed for three U.S. presidents, been nominated for six Grammy Awards, and been the subject of multiple PBS specials. Bell, who over the years performed several free concerts in Bloomington, recently announced that he is co-developing a digital curriculum for violin-learning software app Trala.

Bell was one of several distinguished alumni who returned to celebrate the opening of the Bess Meshulam Simon Music Library and Recital Center in 1995, a renovation of the School of Education building that provided the School of Music with new offices and classrooms, a consolidated space for its music library, and two new performance halls. Webb retired two years later, in 1997, having seen much of what he hoped for and envisioned come to fruition.

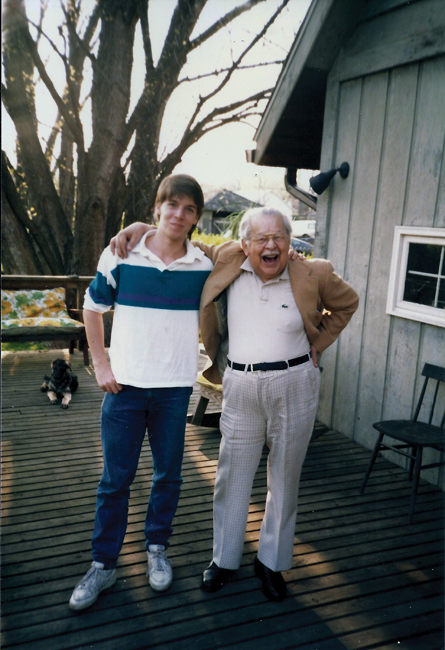

“Charles was a great dean,” says Upper. “He was right in the middle if it all. He performed with faculty, he took students into consultations constantly, he was in the hallways, he was there.” To underscore the personal touch that Webb had as a leader, Upper shared that Webb has also been the organist at First United Methodist Church in Bloomington for 62 years. “Charles, being the choir director, had a lot of students in the choir and one of them befriended Charles a bit—it turned out to be David Jacobs—and that has been a lasting lifelong friendship.”

David Jacobs. Photos courtesy of IU Archives

Barbara Jacobs.

New millennium, new name

David Jacobs Jr., who had studied organ and befriended Dean Webb, suggested to his parents, Barbara and David (both IU grads who became major figures in Cleveland, Ohio, real estate and development), that they bestow a major gift to the music school, which he loved dearly. In 2005, the Jacobs’ $40.6 million gift was the largest ever given to a school of music at a public university, pulling it from the ledge of financial uncertainty into a place of growth. The name was changed to the Jacobs School of Music in tribute.

“There isn’t anything that we built in these last 20 years that wasn’t supported by philanthropy,” says Richards. “And by all of the people who care about what we do and how we do it. Everybody just made a step forward to make possible the Joshi Recording Studio, Marching Hundred Hall, The Studio Building. It’s remarkable how people have stepped up and seen what we really needed to be able to offer the premier education that we’re providing.”

Relevance in the community

Jeremy Allen, the Jacobs School’s current interim dean, grew up in Bloomington and studied trombone with teachers from the School of Music long before he attended the school as an undergraduate. A Grammy-nominated bassist who went to graduate school at the New England Conservatory, he returned to Bloomington to become an associate professor in jazz studies in the mid-2000s and perceived that as much as the school still played in the groove of its history, it continued to embrace the new.

“The Jacobs School has always, in my experience, been far out ahead of the sort of technological changes that are coming into play in the industry and in academia,” he says. “What I noticed when I returned to Bloomington was how impressive our technological capacity was compared with the other institutions I had been in—the media digitization activities that were going on in the Music Library, the access to MIDI [Musical Instrument Digital Interface] and computer music workstations, the incredible development of our recording studio capabilities, which have kind of culminated in the Joshi Studio.”

One area that Richards was passionate about expanding was the relationship with the larger community. “We used to say that we want to be more and mean more to more people; to be more relevant today than we were yesterday and be more relevant tomorrow in society than we are now,” says Richards. The Fairview Violin Project at Fairview Elementary School, which was established in 2008, provided music education to its first graders and has since expanded. “It began with Fairview determining what they wanted to do as we figured out what could we do, how could we be an artist to this value to the community and co-develop something so we could be there for the long term.”

During Richards’ tenure, the Jacobs School moved toward increasing its relevance in multiple ways, from interdisciplinary partnerships with other schools and departments at IU to the new ways that its Office of Entrepreneurship and Career Development helps students imagine their lives after school. But he’s also hopeful—based on the projections of sociologists—that the world is ready to turn to the “expressive arts” for help.

“We need to get outside of our cultural caves,” he says. “If you expect the audience to find you, you’re going to be in trouble. You need to go to where people are, where people are gathering, and you have to make a compelling case artistically—so much so that people want to be a part of it, so they want to do more of it. And the onus is on us to be able to to connect.

“It’s always seemed to us that the way you make a world divided closer together, is to use soft diplomacy—people to people—because those relationships last. It has always felt to us that the arts and culture are a stronger, better way to do it. One of the things that we’ve always hoped for is that there would be a change in our outlook about the role of culture in bringing the divided world closer together. That’s always been felt by us to be a potential way to be more relevant in the world.”

The post-pandemic horizon

Since the Jacobs School holds an average of 1,100 concerts per year on campus and throughout the Bloomington community, the pandemic “has been fraught with all manner of difficulties that that one does not usually face,” says Allen, who stepped into his role in the summer of 2020. “So much of what we do involves producing aerosols and spreading them into the room— so whether you’re singing or breathing and playing a tuba, or dancing, we have to be particularly careful about what we do.

I feel like this last year has just required an incredible amount of attention to every little detail. One year of pandemic dealing feels kind of like three years of administrative work.”

“But the last year was an inspiring year in many ways, because we learned that the commitment that all of our faculty and students and staff have to the school and to doing what we do is very deep,” Allen continues. “Everyone took great personal responsibility, took great care, and we actually were able to make a lot of music, and to hold our classes and to put on operas and put on ballets and to really be very active, to a very large extent last year, more so than many of our peer institutions … and we were able to do so safely.”

Online performances also brought new audiences to Jacobs’ musicians. “One of the things the pandemic has done is certainly made us much more aware of how we can reach well beyond the borders of the campus,” says Richards. “It will be interesting to see what we do as we gather. Will we continue to engage with those who are not collegiate, not degree-oriented, not residential, in a way that we hadn’t prior to that?”

Jacobs has also hired its first diversity and inclusion coordinator. “We’re looking toward doing the work that it will take to make this school an inclusive and welcoming and equitable and diverse environment,” says Allen. “Our course offerings are very broad, and we offer deep and comprehensive training in many different areas, but we want to make sure that we are offering a diverse and inspiring and illuminating palette of course work and that we are as open and welcome to every student who wants to seek training at this level as possible.”

As the fragile potential for reopening and live performance looms, Allen sees the school’s enduring success on continuing to honor its past while trying to help create a new future.

“If you look in particular at the last 70 years of the School of Music, what you see is that our character is to always be moving in this kind of direction where we are taking advantage of the resources and the possibilities that this critical mass of infrastructure, facilities, and outstanding musicians make possible,” he says.

“The Jacobs School is a really strong opera school and a really strong jazz school and a really strong classical performance school, and a strong music education, musicology and music theory school—all of these areas of study have been really strong, so it’s not so much that we want to change things, it’s that we never want to feel like we’re training students for yesterday’s environment. We want to feel like we are training students for tomorrow, and maybe more importantly, training students to be the ones who will determine what tomorrow’s environment will be.

The Berkshire Quartet was the university’s resident string quartet. It included (l-r) Urico Rossi, Albert Lazan, Fritz Magg, and David Dawson. Photo courtesy of IU Archives

(right) Associate Dean Mary Wennerstrom. Photo courtesy of the William and Gayle Cook Music Library

A publicity poster for a 1937 recital by composer, conductor, and pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff. Photo courtesy of the William and Gayle Cook Music Library

David G. Woods was dean of the music school from 1997–1999. Photo courtesy of IU Archives

From 1949–1976, the IU School of Music performed Parsifal by Richard Wagner, bringing worldwide attention to the school. Photo courtesy of IU Archives

Greek-French music theorist Iannis Xanakis in the music school’s Center for Mathematical and Automated Music—now evolved into the Center for Electronic and Computer Music—that he founded in 1967. Photo courtesy of IU Archives

A 1925 flyer promoting performances on the IU campus by John Philip Sousa and his Band. Photo courtesy of IU Archives

Merrill Hall, the first building constructed to house the School of Music, was named after its first dean, Barzille Winfred Merrill. Photo courtesy of IU Archives

Local violin prodigy Joshua Bell had already performed at Carnegie Hall and signed a re- cord deal by the time he became a student at the IU School of Music. Photo by Chris Lee

Wow, not a single word about the internationally acclaimed harp department nor the famous International Harp Competition……

Wonderful article! However, I am disappointed that the Professor Susann McDonald and the U.S.A. International Harp Competition were not mentioned. This is a major competition that has launched many careers for professional harpists. IU’s excellent (and huge) harp department should not be ignored! Perhaps you can feature an article about the competition the next time it is held. Thank you, Anita Clark Jaynes, BM, 1977

Hi Anita, thank you for your comment! Our writer spoke with many individuals at Jacobs before writing this story, and we couldn’t possibly have included all the high praises they gave for the music school’s many programs within the space we had available for this feature. However, a story on the next International Harp Competition is already in the works here at Bloom.

Please don’t forget recently retired Distinguished Professor of Harp Susann McDonald and the USA International Harp Competition she founded at Indiana University!

I was a competitor in the First International Harp Competition held at the IU School of Music. It’s very disappointing that you ignored one of the pre-eminent harp programs in the country while writing this article.

How is it that you managed to totally ignore the HARP department?!?