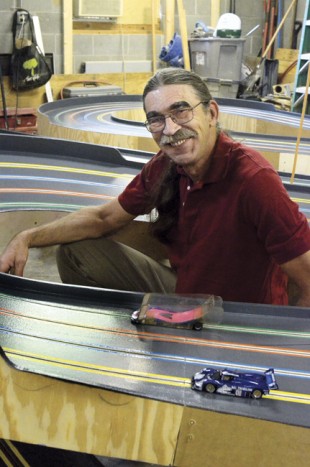

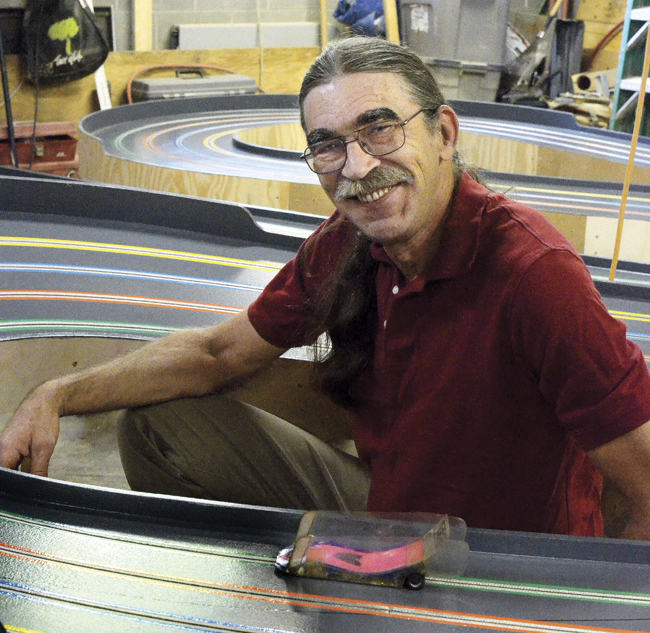

Chris Dadds. Photo by Lynae Sowinski

BY JEREMY SHERE

Local carpenter and general contractor Chris Dadds specializes in what he calls “work with an emphasis on the strange and unusual.” Among Dadd’s many projects—including bathroom and kitchen remodeling, garden structures, and energy-efficiency upgrades—none is more unusual than his longtime passion: building slot car tracks.

“They are pretty much incredibly large pieces of furniture upon which grown men race toy cars,” says Dadds, 58, who has been building tracks since the late 1980s and is one of the foremost track builders in America. At around 21 feet across and 50 feet from end to end, the average slot car track is indeed large. Or, as Dadds puts it, “not something you typically find slid underneath the bed.”

Dadds first got involved with slot cars as a kid growing up in Indianapolis in the 1960s, when the hobby (involving remote-controlled model cars raced on tracks with electrified grooves, or slots) was at its apex. In 1984, when an accident left Dadds with some time on his hands, he returned to slot car racing, which had experienced a revival after subsiding during the ’70s. The local racetrack in Indianapolis, though, was subpar, so Dadds teamed with a few local enthusiasts—they supplied the materials and space, he supplied the carpentry expertise—to build a new track.

Encouraged by the project’s success, Dadds put an ad in a national slot car magazine and soon began receiving orders for custom-built tracks. Charging from $3,000 to $20,000 per track (depending on the size and complexity), what began for Dadds as a hobby suddenly became a viable career.

“I was successful because I approached building tracks like an artist would a painting or sculpture,” Dadds says. “I made sure that my tracks were not only very smooth and well built but also beautiful to look at. I wanted them to be attractive to people who knew nothing about slot car racing.”

Although the slot car revival largely petered out by the late ’90s, today Dadds still builds three or four tracks per year. “Everything I do—from building slot car tracks to doing custom framing and room reconfigurations—is a way for me to express myself,” he says. “I may not be able to make a living as a conventional artist, but I can still express my artistry.”

Chris, long forgotten the author but recall a book on art history speaking of the need to make things special as basis for all art…your work clearly stands the test…good on .you…

John…

British Columia Canada

Great article about a great guy! Happy to know ya, Chris!

Chris has always been known for his slot car sets. Glad to see him getting some recognition

Hi Chris, lets talk, I might be able to use your artistic expierence in FL looking to open a track/hobby shop. You can call or e mail. Heres my # 347 738-1076 My God bless Sincerely Andre

Chris, you certainly bring the strange and unusual. I like the idea of art in construction even slot car tracks that are beautiful to look at and use. Great article and glad to know ya.

I think we have a Chris Dadds mini kingleman. Its the most fun track I’ve raced on in 50 yrs of racing. The Slot Shop, Salt Lake City,UT. 801-792-7973

Chris built a couple of really great tracks for me back in the late 90s. i think they are still in use last i heard. i enjoyed meeting him when he delivered them. https://www.facebook.com/robert.laffoon.5

Chris, I’ve seen some of your tracks and they ARE works of art! Hope you continue to build the best slot track’s in the world. Best Regards.