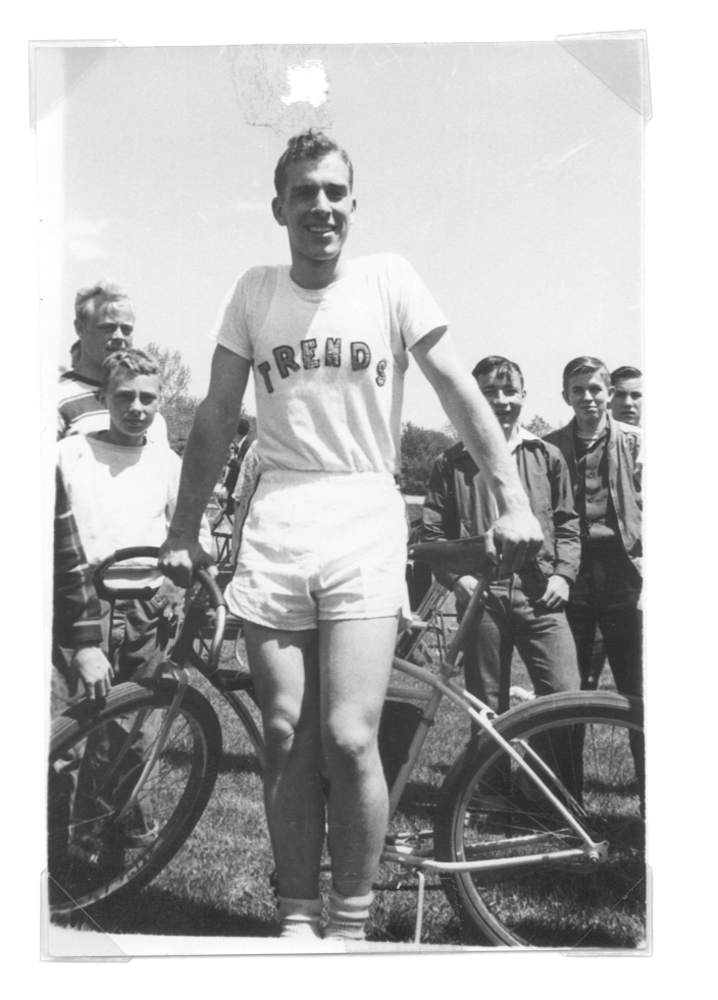

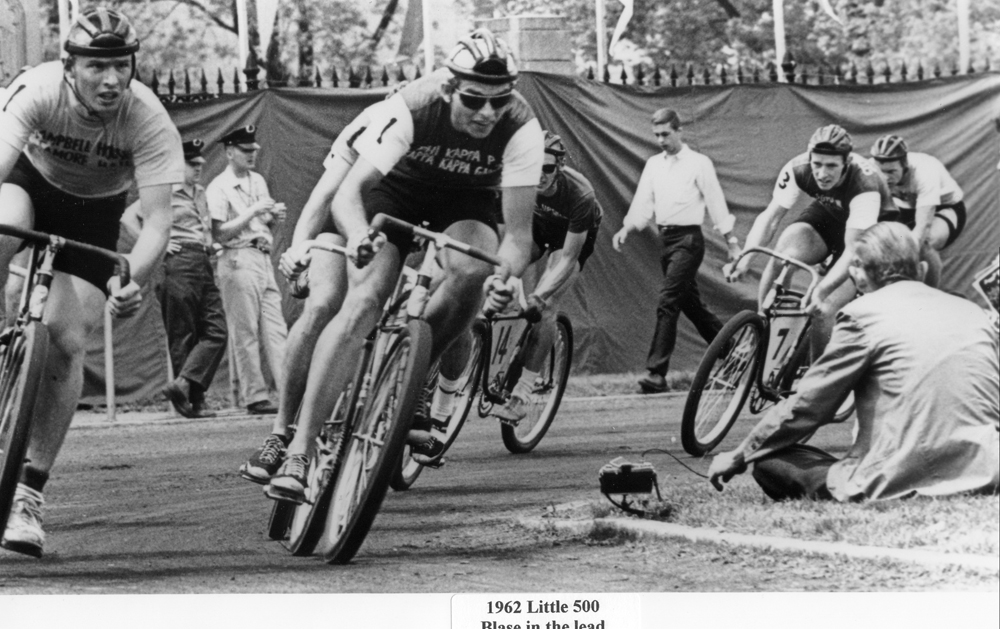

Little Five’s humble beginnings. Photo courtesy of the Indiana University Student Foundation

In anticipation of Indiana University’s annual Little 500 bicycle races this weekend, we bring back this feature story from our February/March 2011 issue.

BY ELISABETH SANDERS

In its 60 years, the Little 500 phenomenon has been a boon and a bane to Bloomington, but the event is on the right track again.

Little 500 has been called the “World’s Greatest College Weekend,” and in some ways it’s what has put Bloomington on the map. What other student event, after all, has inspired an Academy Award-winning film like Breaking Away, or consistently drawn A-list celebrities such as Bob Hope, Lance Armstrong, and Barack Obama. Nowhere else has an intramural contest captured such national attention and attracted crowds that at times exceed the whole of the student population.

Yet, for Bloomington residents, Little 500 can bring forth a range of emotions. While many embrace the tradition, others tend to flee from the festivities, fearing the worst effects of a “college weekend” in overdrive.

Inside the stadium, though, the race’s focus has never faltered. For 60 years, through countless cultural shifts and unpredictable media attention, Little 500 has continued to fulfill its original purpose: raising funds for student scholarships through a dedicated athletic event that both enriches participants’ university experience and provides spectators with an atmosphere of unparalleled excitement.

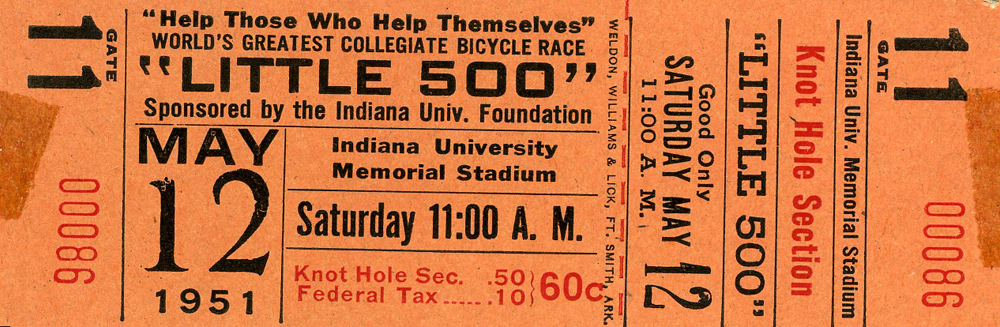

Saturday, May 12, 1951

The 1951 Little 500 logo.

Jerry Ruff remembers reading the announcement in the Indiana Daily Student. The newly formed IU Student Foundation Committee (now IUSF) was putting on a bicycle race that would take place that May, 1951. The event would pit the men’s housing units against one another in a contest modeled after the Indianapolis 500 auto race. It didn’t take a minute’s hesitation for Ruff to start planning a team.

“It was a wonderful idea, and it spread quickly,” he recalls. “It was easy for me to stir up interest. I was living in North Hall—what’s now Collins Hall North—and we had a team called the Friars. We had a couple of super athletes in our dorm and we figured we’d do well.”

The race, dubbed the Little 500, was the brainchild of Howard S. “Howdy” Wilcox, executive director of the IU Foundation. Wilcox had racing in the blood, as his father had won the Indy 500 in 1919. When the younger Wilcox happened upon a group of students riding bicycles around their dormitory in a lighthearted test of skills, he knew he had found the perfect event to get students involved in his foundation.

Wilcox drew on his Indy 500 connections to make the first race a proper spectacle. As John Schwarb chronicles in his book, The Little 500: The Story of the World’s Greatest College Weekend (Indiana University Press), from the driver of the pace car to the man waving the checkered flag, Wilcox essentially transplanted the staff of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway to IU’s old Memorial Stadium. Though the bicyclists would ride 50 miles instead of 500, they too heard the voice of Indy 500 announcer Sid Collins and were shepherded by the speedway’s chief steward, Tommy Milton. Likewise, a roaring crowd of some 7,000 spectators turned out to cheer on the riders on Saturday, May 12, 1951.

Among those supporters were the women of Indiana University, whose role in the early years was to make riders’ outfits, decorate their pits along the track, and generally serve as cheerleaders. Ruff recalls, “The Tri Delts made our little checkered trunks and our T-shirts. They really got into it.”

Despite this enthusiastic backing from the co-eds, one team clearly outshone the rest on that first race day. The South Hall Buccaneers won by more than a mile, finishing in 2 hours 38 minutes, four and a half minutes ahead of the second-place team. The reason? They were the only team to train in an organized fashion.

A ‘cute event’

The first-ever winning team, the South Hall Buccaneers. Photo courtesy of the Indiana University Student Foundation

Ruff left Indiana in 1954 for military service, and by the time he returned two years later the race was a different animal. Training had become a matter of course, attendance at the event had tripled, and a fraternity’s social standing was beginning to be measured in terms of its Little 500 prowess.

Meanwhile, the women had established their own race, the Mini 500. Held in the Wildermuth Fieldhouse, it featured a team relay at top speed—on tricycles. With prizes awarded not only for top finishers but also for best dressed and for best floats in the pre-race parade, it was what Ruff described as a “cute event.”

Another shift was Wilcox’s replacement by Bill Armstrong, who labored to round out the weekend with a number of other attractions. The Little 500 Extravaganza, a free concert held the Friday before the race, would feature the likes of the Four Lads, the Kingsmen, and Chicago. The Little 500 Variety Show, a ticketed Saturday night event in the IU Auditorium, brought in Connie Francis, Andy Williams, the Smothers Brothers, and Hoagy Carmichael. Armstrong would also recruit a succession of celebrity “Sweethearts,” mostly singers and beauty queens whose primary role was to bestow kisses on the Little 500 winners.

A level playing field

Throughout the ’60s and early ’70s, the event was extraordinarily successful by nearly all measures: participation, attendance, and its original goal of funding scholarships for working students. Where IUSF struggled was in keeping a level playing field that would allow any team a fighting chance to win.

From the start, IUSF supplied the bicycles for the students, thinking this would eliminate any team having an advantage based on finances. No one anticipated the costs that would come with increasingly sophisticated racing gear or the soon-to-be- common practice of training in Florida over spring break.

Likewise, no one foresaw that fraternities would begin recruiting national-level riders to their teams. In response to participation by superstar cyclists like Karl Napper, Dave Blase, and Eddy Van Guyse, IUSF repeatedly tweaked its eligibility requirements to try to keep the world’s best riders off the IU track. One coach observed in 1974 that Olympic cyclist Wayne Stetina participating in the Little 500 that year was like Mark Spitz swimming for an IU intramural team.

In 1978, IUSF determined that athletes designated by the United States Cycling Federation as Category One (professional) or Category Two (semi-pro) would be ineligible for the race. Though the “Cat 2” rule has gone back and forth over the years, this measure has gone a long way toward keeping Little 500 an intramural rather than a professional race.

The ‘party central’ theme

The decade that followed the ruling transformed “Little Five” from a beloved university tradition to an internationally recognized phenomenon that nearly collapsed under its own weight. Beginning with the success of the 1979 film Breaking Away—based on legendary Little 500 rider Dave Blase, written by his Little 500 teammate Steve Tesich, and featuring cameos by a number of IU personalities including the university president—the nation began to take notice of this unusual intramural event.

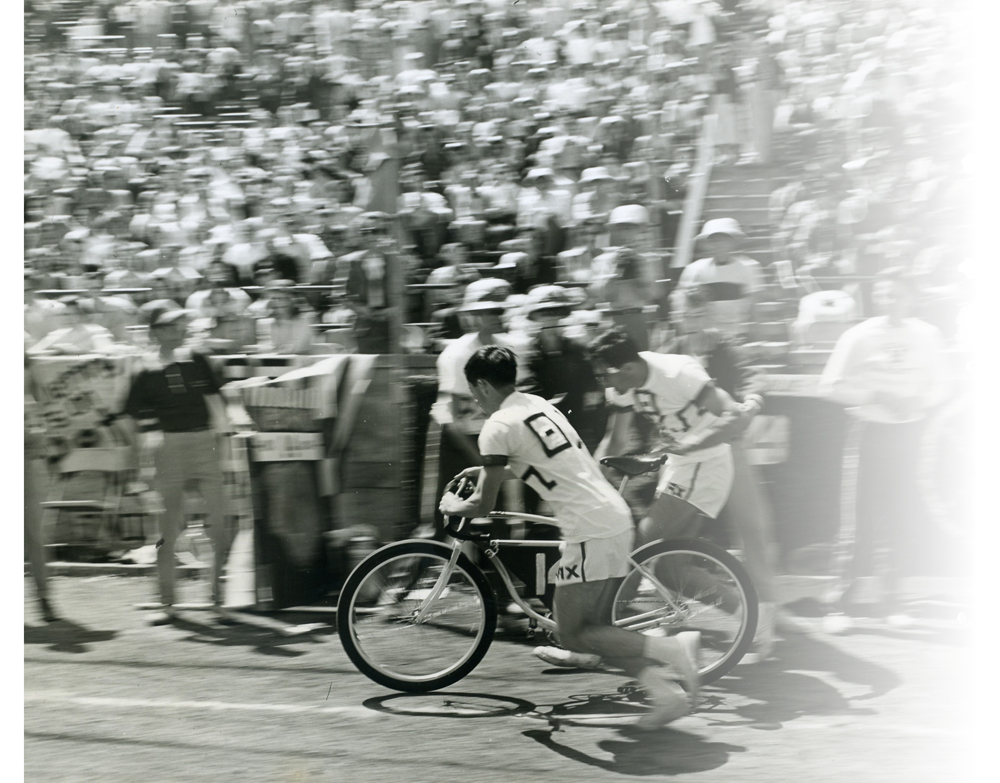

Students gather at the race to support their teams. Courtesy photo

In 1986, Schwarb notes in his book, MTV broadcasted onsite and nearly 32,000 fans filled Bill Armstrong Stadium. That night, more than 50,000 people gathered inside and outside of Memorial Stadium to hear hometown hero John Cougar Me

llencamp close his “Scarecrow” tour. MTV returned in 1987 and ’88, each time focusing at least as much attention on the “party central” theme as the race itself.

MTV sold the story all too well. Out-of-town revelers began flocking to Bloomington looking for a chance to let loose. First in 1988 and then again in 1991 in what came to be known as the “Varsity Villas Riots,” police made hundreds of arrests in response to vandalism, violence, and drinking violations. “There was quite a commotion that even included cars being set on fire and turned over,” says Dana Cummings, the current IUSF director. The majority of the “hooliganism,” according to the Bloomington Herald-Times, was perpetrated by visitors without ties to IU.

“At that point, the race came under incredible scrutiny from university and city officials,” Cummings says. The ensuing police crackdown resulted in crowds diminishing to half their peak in the next few years. Although the foundation suffered a financial blow from this exodus, the organization was eager to cast aside the weekend’s hard-partying image. Following the Varsity Villas incident, it changed its Little 500 slogan from “The World’s Greatest College Weekend” to “Cycling, Scholarships, Tradition.”

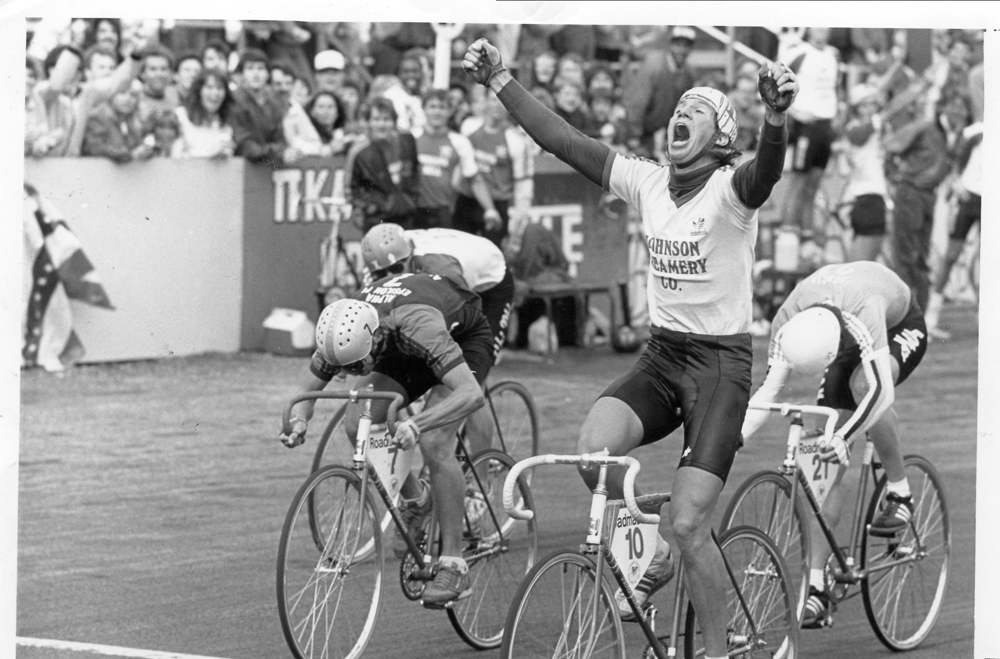

The women qualify

In the midst of the MTV mayhem, another race transformation was taking place. No longer content with tricycles, a team of Kappa Alpha Theta sorority riders made history in 1987 with the first successful women’s qualifying attempt for the race. Though their finishing time was not in the top 33, and thus excluded them from the race itself, “Just the fact that we qualified was a big deal,” recalls team member Martha Hinkamp Gillum.

Buoyed by their groundbreaking achievement, Gillum and her teammate Lee Ann Guzek

Past members of the Chi Omega Little Five team. Courtesy photo

committed to organizing a separate women’s race. “From then on, our main job was to put together teams,” Gillum, 43, says today. “It was a grassroots effort. We went to every residence hall and sorority. It turned out there was a lot of pent-up interest.

At last, in 1988, the first women’s Little 500 took place the Friday before the men’s race. To help overcome barriers to participation, it was set at 100 laps instead of 200. Otherwise, the race mirrored the men’s in every way.

“It was fantastic,” says Gillum. “It was so satisfying, because the race was our baby. But I think it would have happened without us, it just needed somebody with enough guts to see it through.”

The present

Today Ruff, now 80 and the father of Bloomington City Councilman Andy Ruff, says he prefers the women’s race to the men’s. It’s more competitive, he argues, as the Cutters men’s team has dominated the track with a record-breaking four wins in a row. (Though named for the townie team in Breaking Away, the Cutters and all Little 500 riders are full-time IU undergraduates.) Both races, though, continue to draw substantial crowds with more than 20,000 fans turning out over the course of the weekend. In the last decade, a “Little Fifty” running relay, consisting of 50 laps around the IU track-and-field arena, has also attracted hundreds of runners each year.

Thanks to improved technology and training, the race has gone from 18 mph to 25 mph. But the race is still 100 percent human powered. Courtesy photo

IUSF is happy with the event’s more limited attendance in contrast to its rowdier days. Little 500 continues to raise some $38,000 each year for student scholarships and to benefit from more than 200 volunteers acting as coaches, scorers, ticket takers, safety officials, and in a range of other roles. Riders overwhelmingly report that their Little 500 experience is the most rewarding of their college years. Pam Loebig was so inspired by riding in 2006, ’07, and ’08 that she now works full time as the race’s primary organizer.

One issue, however, still troubles the organization. Ever since the disruptions 20 years ago, the race has been plagued by a reputation for out-of-control partying that leads many Bloomington residents to avoid the event, if not to leave town altogether. Cummings says if she could change one thing about Little 500, it would be to have residents realize that the race itself bears no resemblance to this unruly image.

“If you buy a ticket and come inside Armstrong Stadium on race day, you’ll find that it really doesn’t have anything to do with partying; rather, it has to do with scholarship, and a bunch of incredibly committed athletes competing alongside their classmates,” she says.

For Autumn McCoy, a local resident who has served as both a coach and a security guard at Little 500, Cummings’ words couldn’t ring truer. “The dedication and the commitment of the athletes is just incredible,” she says. “My son and my grandson also come to watch the races, and everyone loves being a part of it.”

Check out more images from Little Five’s history in the gallery below. Courtesy photos (Click on the photo below to start the slideshow. Use the on-screen arrows or the arrows on your keyboard to navigate forward and backward.)