by JULIE GRAY

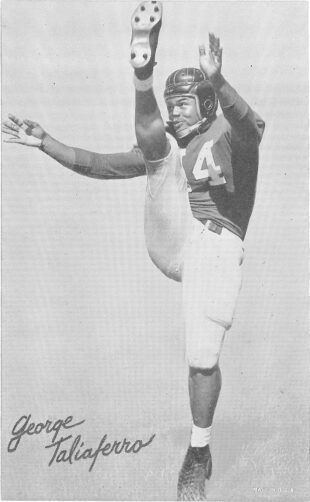

In Race and Football in America, Dawn Knight traces the impact that the late Indiana University football hero George Taliaferro had on her and many others, as well as on the game of football and the civil rights movement.

Knight, an IU alumna, met Taliaferro when she took his introductory social work course at IU in 1991. She originally published her book in 2007, and this new edition had not yet appeared when Taliaferro died in October 2018 at the age of 91.

The second edition of the book was occasioned by fresh material Knight uncovered about Taliaferro and by the controversy that followed when former San Francisco 49er Colin Kaepernick knelt during the national anthem to protest racism and police violence. “I wondered,” Knight writes, “at the absolutism of the responses, at the lack of an attempt to understand one another.” She hoped that retelling the story of how Taliaferro had used football as a platform to combat racism would be illuminating.

When she asked Taliaferro about Kaepernick’s decision to take a knee, he told her he didn’t want to think about it because he knew what Kaepernick was going through. Then, he added, “The one word I could use and really mean is ‘hopeful.’” In her book, Knight shows why Taliaferro had reason for hope.

When he arrived in Bloomington in 1945 to play football for IU, black students couldn’t live or eat on campus, and Bloomington restaurants weren’t open to them. If they wanted to see a movie, they could do so only at certain times and had to sit in restricted sections. With the help of then-IU President Herman B Wells, Taliaferro changed those practices, usually by simply walking into a restaurant and taking a seat. All his life, Taliaferro kept the “Colored” sign he had unscrewed from the wall of the Princess Theatre on North Walnut Street the night he integrated it. His stature as a sports hero gave him a freedom that, it turned out, extended to all black students.

After being the first African American player drafted by the NFL and playing professionally, Taliaferro went on to earn a master’s in social work at Howard University. He also married the former Viola Jones, whom he had met while in the Army. During their first lunch together, he was so smitten that he claimed to have absolutely no memory of whether he’d actually spoken or eaten.

Viola Taliaferro was later a Monroe County circuit court judge. In an epilogue, Knight writes of her visits to the retirement home where George and Viola, who suffers from dementia, lived. On one such visit, George, who was sitting in front of the building with his walker, hurried her in, saying, “I want you to meet my girl.” Clearly, love, as well as hope, infused his life.

Since his passing, Indiana University has honored Taliaferro by naming Memorial Stadium’s north end zone plaza in his honor. The George Taliaferro Plaza is a fitting tribute to the late Hoosier athlete who shattered racial barriers in football, on campus, and in Bloomington.