by MIKE CAGLE

While many people in Bloomington know me as an artist and illustrator, several years ago my life took a drastic turn and I, in turn, decided to head to law school in Portland, Oregon. After successfully passing the bar, I began my job search. It took a year.

Fate is a cruel jokester. Among the things I had always hated about Indiana were its cold, icy winters. The job I finally found was in Kotzebue, Alaska—30 miles north of the Arctic Circle.

Kotzebue (pronounced KOTS’-uh-bew and called “Kotz” by just about everyone) is situated in an area of mudflats and shallow water where rivers meet the sea. Such places are rich in natural resources and well-situated as regional trading hubs. The Kotzebue region has been inhabited for more than a thousand years and, long before the arrival of Russians and Europeans, has been a trading center visited by people from as far away as Siberia.

Kotz is unlike any place I’ve ever been. There are about 3,300 residents, 70% of whom are indigenous Alaskan Natives. With no roads in or out, Kotz is effectively an island (though technically it’s on a peninsula). Everything that comes into Kotz comes by plane or barge.

The physical and constructed environment of Kotz is spartan. There are no trees. The architecture is strictly utilitarian. There is no bookstore, barbershop, hair salon, coffee shop, bar, movie theater, music venue, or veterinarian. But, wonder of wonders, there is an NPR station! Public radio is important in rural Alaska because the economy is too sparse to support commercial radio.

In midsummer, the sun doesn’t set. In deepest winter, the sun is up for about two and a half hours—but it doesn’t rise very far above the horizon, and the sky is frequently overcast, so the effect is a dim period of twilight before night returns. Temperatures in winter can sink far, far below zero. Sometimes there are blizzards. Sometimes there are northern lights.

The past two winters, I’m told, have been somewhat less cold than they used to be—and much snowier. Sea and river ice forms later and breaks up earlier, sometimes with deadly and tragic consequences. The summer has been warmer than usual, too. A sea wall was installed along Shore Avenue because waves were damaging the street. Like every town at sea level on a coast, Kotz’s days are numbered. I have a ringside seat for climate change.

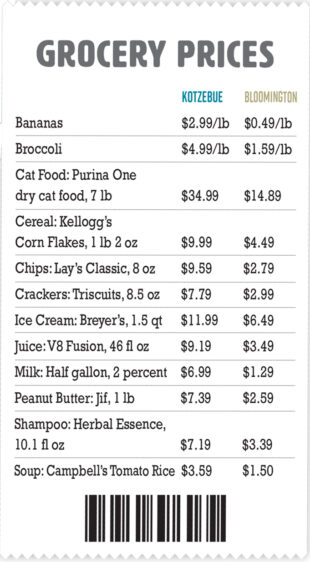

The cost of living is extremely high. My job pays well on paper, but it’s a challenge to make ends meet. Items in the town’s two grocery stores often cost two or three times what one would pay in the lower 48 [see sidebar]. It’s a tough place to be poor, but there are poor people here.

We actually can’t see Russia from here, but it’s not far away. A few miles outside of town is a NORAD radar station, which was staffed by the Air Force during the Cold War; I believe it’s totally automated now. I’ve heard more than one person describe their genealogy as “half Eskimo, half Air Force.” They never knew their biological fathers.

Job-wise, I was lucky to stumble into a fairly low-pressure, supportive environment in which to learn legal skills as a beginning lawyer. My role is to help low-income clients with civil matters like divorce, child custody, adoption, wills, and so on. And beyond the work, I’ve learned a lot from living someplace so different from anywhere I have ever lived before.

But there are a few things that are very similar to small-town, southern Indiana. There are lots of churches. Most people own guns. Basketball is the most popular sport, and high school basketball, in particular, is a beloved, community-building attraction. And, really, there aren’t many other options for entertainment. That’s why I attended a game. I was oddly cheered to see that the colors of the Kotzebue Huskies are blue and gold, the same as my old high school team, the Brown County Eagles. And, for a while on that cold evening, no matter how strange things seem most of the time, I almost felt right at home.